Western Banks and the Rise of Parallel Financial Systems

The growing risk of illicit and sanctions-evasive liquidity embedding Into global capital markets

Image from a previous police raid on Deutsche Bank that occurred in 2018

On January 28, German police prosecutors raided the Berlin and Frankfurt offices of Deutsche Bank, the largest financial institution in the country. The surprise raid came just one day before the company was set to release its 2025 earnings report, causing share prices to immediately plummet by around 3%. At least 30 plainclothes investigators entered the offices around 10am local time, targeting a “yet unknown” number of employees. According to prosecutors, their investigation surrounds companies suspected of money laundering on behalf of entities tied to sanctioned Russian oligarch, Roman Abramovich.

This raid is illustrative of a much broader trend.

The last few years have delivered a steady slew of headlines about major law enforcement actions against banks suspected of money laundering and falling prey to criminal influence. Last year, the U.S. Treasury made the unprecedented move of sanctioning three Mexican banks as a primary money laundering concerns in connection with opioid trafficking. In 2024, Canada’s TD Bank agreed to pay a record $3 billion in fines in connection with money laundering for the Sinaloa and other Mexican drug cartels; Canada’ FINTRAC imposed nearly $10 million in additional fines against the bank. Crypto exchanges are at the front lines of such punitive measures, with Binance agreeing to pay a $4.3 billion in fines and restitution in a 2023 deal with US regulators enforcement. Last year, FINTRAC imposed a record $177 million in fines against crypto exchange Xeltox in connection with darknet markets, child abuse, fraud, and ransomware.

These are not compliance failures, but failures of perception. Institutions are operating with risk models built for a world in which illicit finance was episodic, traceable, and external to core liquidity systems. That world no longer exists.

While laundering techniques evolve incrementally, detection regimes evolve retroactively. Capital that clears today under acceptable assumptions is increasingly reclassified tomorrow as sanctionable, tainted, or facilitative. Institutions that do not adapt in advance are not merely exposed — they are accumulating latent enforcement risk they cannot unwind. Evidence suggests the consequences are increasingly unaffordable, prompting the need for proactive measures.

Shwe Kokko, Myanmar: built in a civil war and financed through Chinese state investment, the multi-billion-dollar militant-backed city now serves as a notorious hub for cyber scammers.

Parallel financial infrastructures

Massive, parallel liquidity architectures now operate alongside regulated global financial markets. These systems emerged to serve actors excluded from the formal financial system and have proliferated amid rapid fintech innovation, tightening sanctions regimes, and rising geopolitical polarization.

Strict capital controls, combined with sustained political and economic instability, have generated large and unregulated capital outflows from high-stress jurisdictions such as China, Russia, and Iran. These outflows create primary demand for parallel financial infrastructure, supplying the early liquidity needed to establish and scale shell companies, grey-market digital exchanges, trade-based money laundering mechanisms, and over-the-counter (OTC) crypto brokerage networks. Under sanctions pressure, state-linked actors within these jurisdictions also rely on such channels to export goods and procure restricted or dual-use technologies beyond formal oversight.

These parallel architectures are not used exclusively by state-linked elites or individuals engaged in capital flight. Organized criminal groups—including Latin America drug cartels, Chinese-run scam syndicates operating across Southeast Asia and Africa, and European networks such as the ’Ndrangheta—exploit the same ungoverned financial rails to move and launder proceeds.

The systemic risk lies not in any single actor, but in the laundering capacity of these parallel systems themselves. Although designed to operate outside regulatory oversight, these infrastructures ultimately interface with—and depend upon—safe, well-regulated financial markets. Capital originating in capital flight, sanctions evasion, and organized crime frequently converges at the same intermediaries and settlement points before being absorbed into Western asset markets.

For example, Chinese money laundering networks (CMLNs) facilitate the laundering of bulk cash generated by Mexican drug cartels, with funds ultimately settling into U.S. asset portfolios held by wealthy Chinese households seeking capital externalization. Similarly, infrastructure projects financed under the Chinese state-run Belt and Road Initiative have, in certain jurisdictions, contributed to permissive governance environments that organized criminal groups exploit to establish large-scale cyber-scam operations, ultimately moving wealth out of the country and into private hands elsewhere. Once laundered through the region’s vast ecosystem of casino gambling hubs and international shell corporations, these funds may be invested in Western markets like Australia or the United States.

Elsewhere, Iranian regime-linked elites have accumulated extensive international property portfolios in Western countries using shadow financial infrastructure associated with the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps and its affiliated networks. In Europe, criminal organizations such as the ’Ndrangheta rely on the same real-estate-based laundering channels in Turkey and offshore banking access points in Cyprus that have long been used by Russian elites to externalize wealth and sustain financial activity under sanctions pressure. Recent evidence also indicates that Russian state-owned factories increasingly supply Italian mafia groups with unmarked weapons via shadow fleet vessels, demonstrating that these informal networks can produce violent consequences.

Across these cases, the common denominator is not coordination between actors, but the repeated reuse of resilient parallel financial infrastructure that channels capital back into regulated Western markets. Funds associated with criminal or terrorist activity are placed through multiple layers—including casinos, online gaming platforms, real estate, and front companies—before being progressively cleaned and integrated. The result is not a segregated illicit economy, but deep structural integration between unaccountable liquidity systems and the global financial core.

Exposure

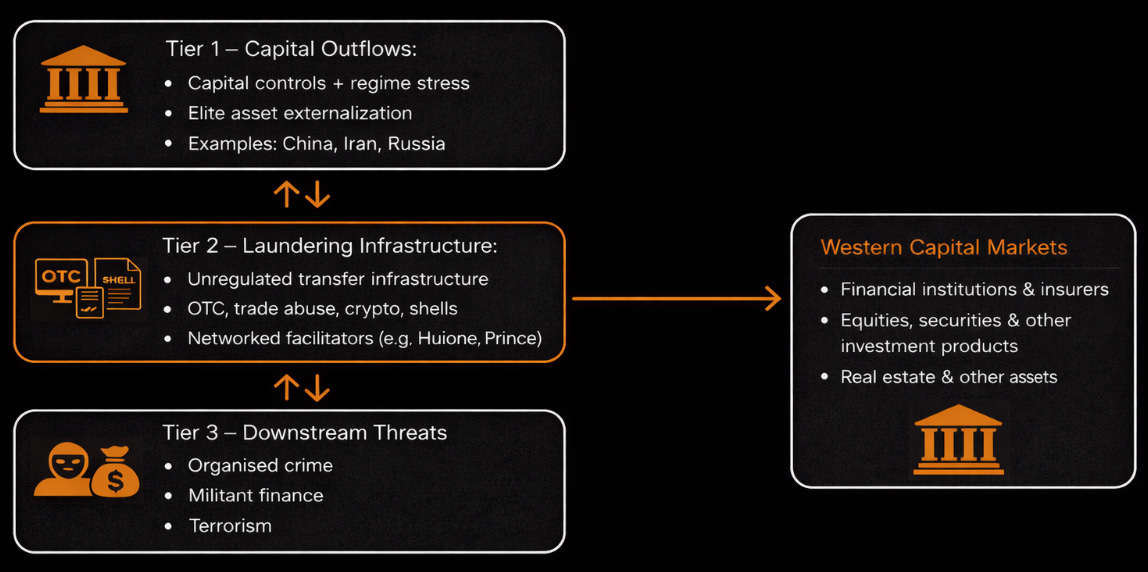

The three-tiered architecture clarifies the exposure to Western banks and other institutions:

Figure 1 illustrates a three-tier liquidity architecture showing how parallel financial systems interact with regulated Western capital markets.

Tier 1 captures upstream capital outflows from high-stress jurisdictions shaped by capital controls, sanctions pressure, and regime instability. Driven primarily by elite asset externalization and state-linked value movement, these outflows provide much of the initial liquidity that seeds parallel financial systems due to the volume of demand they represent.

Tier 2 represents the midstream laundering infrastructure that enables these flows to move and settle outside formal regulatory oversight. This layer includes OTC brokers, trade-based money laundering, shell companies, grey-market digital exchanges, and related facilitators that function as shared financial rails used by state-linked elites, criminal networks, and sanctioned actors alike.

Tier 3 encompasses downstream threat actors. Including organized crime groups, militant organizations, and terrorist networks. These groups frequently exploit the same infrastructure to move and launder illicit proceeds.

The diagram highlights the bidirectional interaction between tiers, reflecting how upstream capital flight sustains laundering infrastructure while downstream criminal activity reinforces its profitability and resilience.

The right-hand node illustrates the final stage of the cycle: integration into Western capital markets. Despite originating in parallel systems designed to evade oversight, laundered capital ultimately seeks stability and legal protection within regulated financial systems, creating systemic exposure for financial institutions, real estate markets, and investment products.

The core risk lies not in any single actor, but in the durable infrastructure that links capital flight, illicit finance, and regulated markets into a continuous financial circuit. Most importantly, as global sanctions regimes increasingly target state-linked actors at Tier 1 and non-state actors at Tier 3, exposure concentrates in Western capital markets where funds moving through this infrastructure are ultimately integrated.

Global enforcement vigilance

Global regulators and law enforcement agencies are under accelerating pressure to identify, disrupt, and prosecute financial activity linked to illicit finance. This pressure is no longer cyclical or reputational; it is structural and driven by two converging forces.

First, geopolitical escalation and sanctions enforcement

In an increasingly polarized international environment, illicit financial channels used by adversarial states to bypass export controls and procure restricted or dual-use goods are now treated as matters of national security rather than compliance oversight. As sanctions regimes expand in scope and severity, enforcement agencies are increasingly compelled to pursue not only upstream actors but also the financial institutions through which such activity ultimately settles.

Examples include Russia’s sanctioned war economy, Iran’s shadow banking networks, and China’s underground procurement of restricted military and dual-use technologies.

Second, the trans-nationalization of organized crime

Modern criminal networks are increasingly post-sovereign, operating across jurisdictions and establishing parallel financial systems that erode state authority and undermine global governance. These systems are no longer peripheral; they intersect directly with regulated markets.

Examples include militarized Mexican cartels such as Sinaloa and CJNG, as well as large-scale scam-center enclaves in Myanmar and Cambodia.

Across all domains, political tolerance for inaction is collapsing. Regulatory and law enforcement agencies are increasingly expected to demonstrate tangible results, often through high-profile investigations, raids, and retroactive enforcement actions. In the United States, recent sanctions guidance has materially expanded this exposure: the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control now applies a ten-year enforcement lookback, extending liability to conduct that cleared under acceptable assumptions years earlier. Parallel developments are underway in Europe, where the European Union has moved to harmonize criminal penalties for sanctions violations across member states, signaling a broader shift toward more aggressive and coordinated enforcement.

Because Western banks and capital markets represent the terminal integration point for most large-scale laundering activity, they are not incidental to this process, structurally exposed to it. Capital that once cleared under acceptable assumptions is increasingly reclassified as sanctionable, tainted, or facilitative. Institutions that treat these dynamics as external threats rather than embedded risks are not merely vulnerable to future scrutiny; they are accumulating enforcement exposure that cannot be unwound once political thresholds are crossed.

Technological advances risk further investigatory disruption

Technological advances in machine learning and artificial intelligence are rapidly expanding investigators’ ability to retroactively identify illicit financial networks after they have already entered Western capital markets. While global organized crime syndicates adopted crypto early to bypass traditional regulatory controls, the underlying structure of blockchain systems — which preserve immutable transaction records on public ledgers — has paradoxically made illicit liquidity more traceable over time. As a result, capital that once appeared safely integrated can later be reconstructed, mapped, and reclassified. Blockchain analytics platforms are already deploying advanced AI-driven pattern detection, and DARPA’s A3ML program aims to make large-scale money laundering economically unviable by disrupting these networks at scale.

At scale, AI adoption favors actors with capital depth, institutional expertise, and the protection of the rule of law. While criminals may experiment with tactical obfuscation, these advantages compound over time in favor of investigators rather than illicit networks. Banks and other financial institutions should therefore assume that today’s undetected exposure may become tomorrow’s enforceable liability, rather than relying on money launderers’ ability to permanently conceal financial activity.

Conclusion

The dynamics described here are not temporary distortions or episodic compliance challenges. They reflect a structural shift in how illicit, gray, and state-linked capital moves, settles, and ultimately integrates into the global financial system. Parallel financial infrastructures have matured into durable liquidity systems that operate continuously alongside regulated markets, not at their margins.

Western banks and asset markets sit downstream of these systems. They are not incidental endpoints but the terminal nodes where capital originating in sanctions evasion, and criminal enterprise ultimately seeks stability, legal protection, and yield. As enforcement priorities expand from reputational misconduct to national security risk, and as sanctions regimes increasingly target both state and non-state actors across this spectrum, exposure concentrates precisely where this capital is absorbed.

Crucially, enforcement is no longer prospective. Detection, attribution, and liability are increasingly retroactive, enabled by improved data integration, cross-border coordination, and advancing analytical technologies. Capital that cleared under acceptable assumptions in the past is now subject to reclassification, scrutiny, and enforcement years later. Once political thresholds are crossed, this exposure cannot be unwound.

Institutions that continue to treat illicit finance as an external threat, rather than an embedded feature of modern liquidity systems, are not merely vulnerable to future action. They are accumulating latent enforcement risk that will surface on timelines and terms they do not control. In this environment, resilience depends less on incremental compliance improvements than on a fundamental reassessment—at the board, supervisory, and enterprise-risk level—of how parallel financial infrastructures intersect with regulated markets and where, within that system, exposure is truly accumulating.

This problem is not cyclical, but structural. Western financial markets sit downstream of parallel liquidity systems that are already embedded. Enforcement is increasingly retroactive, not preventive. Institutions that fail to adapt now are not merely exposed to future scrutiny — they are accumulating liabilities that cannot be unwound once political thresholds are crossed.

Really strong framework on the three-tier architecture. The distinction betwen capital flight at Tier 1 and the shared laundering infrastructure at Tier 2 clarifies why enforcement keeps hitting Western banks even when they think they're just dealing with normal capital flows. Ive been watching the TD Bank and Deutsche cases unfold and the retroactive liability piece is what makes this especially dangerous for institutions that haven't adapted thier risk models yet.