Understanding Unregulated Capital Outflows Is Essential in Predicting Tomorrow's Threats

The Financial Mechanics Behind the Modern Threat Landscape

Author’s Note:

This piece is more technical than much of my prior work. It is intended as a conceptual and analytical framework rather than a narrative essay, and is written for readers interested in understanding the structural mechanics of unregulated capital flows and their downstream security implications.

I am publishing it openly in the belief that clearer analytical tools are necessary if institutions are to anticipate and disrupt emerging threats more effectively. Readers who find this work useful, or who are working on related problems, are welcome to contact me directly at info@btl-research.com.

In work published over the past several months, I have emphasized that unregulated capital flows I term “shadow liquidity” consistently manifest as powerful downstream threats. Whether terrorist groups in Sub-Saharan Africa leveraging illicit networks to smuggle resources and procure weapons, or scam centers and drug cartels exploiting complex liquidity architectures, the global shadow financial ecosystem has become markedly more dangerous.

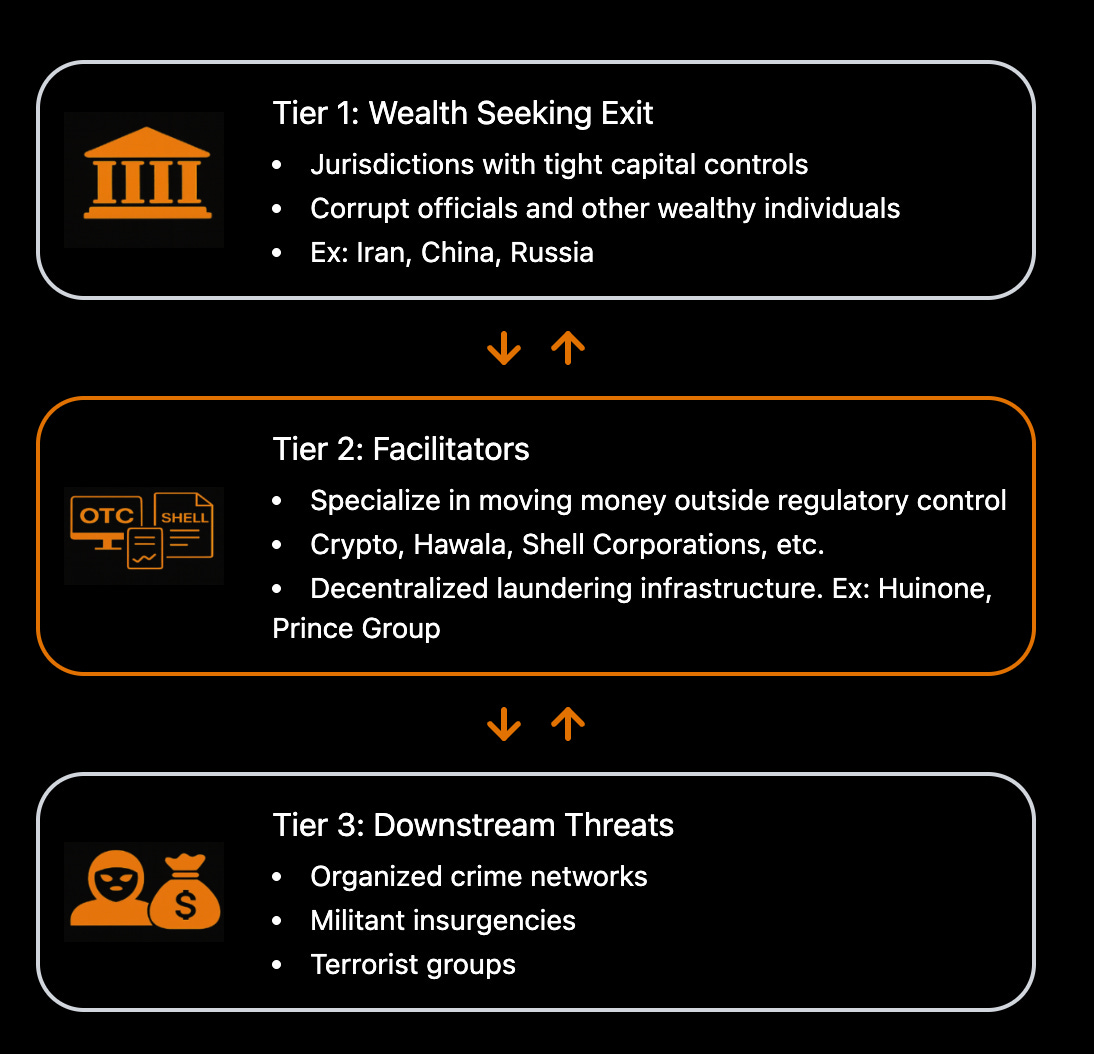

I developed a three-tier framework to explain how these parallel financial architectures operate and why they generate persistent downstream harm. Tier 2 consists of a vast layer of globally connected financial intermediaries that move value outside formal legal and regulatory oversight. Tier 3 sits downstream of these flows and includes criminal organizations, militant groups, and terrorist networks that exploit Tier 2 infrastructure to finance operations and project predation and violence.

Tier 1 is where the threat ultimately originates. At this level, large pools of wealth—often held by corrupt officials, politically exposed persons, and other elites in tightly controlled capital markets—seek to externalize assets to safer jurisdictions. This demand for offshore mobility creates the economic foundation for Tier 2 networks, which are then leveraged by Tier 3 actors, with or without direct state involvement.

These dynamics likely involve hundreds of billions of dollars annually, much of which fuels instability, entrenches criminal economies, and contributes to the impoverishment and coercion of millions of people worldwide. In recent work for the New Lines Institute, I documented how militarized scam syndicates in Southeast Asia and Latin American drug cartels (Tier 3) tap into Tier 2 infrastructure that moves billions of dollars annually in response to Tier 1 demand originating in the tightly controlled Chinese capital market. My most recent work for Between the Lines shows how Iran leverages a similar three-tiered structure to finance its proxy networks and externalize elite wealth.

Each of these systems is inherently destabilizing, not only for downstream societies targeted by criminal and militant activity, but also for the states at the origin point, where capital flight erodes economic resilience and governance over time. For this reason, understanding the origin of unregulated capital flows at Tier 1 is imperative for global security.

The three-tier framework illustrates how unregulated capital flight and its facilitators at Tier 1 and Tier 2 translate into downstream criminal and militant threats at Tier 3.

Unprecedented Speed

This danger is magnified by the unprecedented speed at which unregulated wealth now moves. Since the collapse of Bretton Woods in the early 1970s, global finance has become increasingly interconnected, with cross-jurisdictional transfers occurring in hours—or seconds—rather than days or weeks. Compliance and enforcement frameworks remain largely reactive, disproportionately focused on individual transactional disruption rather than sustained action against underlying networks, ownership, and control structures. The proliferation of shell corporations and offshore banking has further obscured attribution and accountability, while crypto-based decentralized financial systems introduce parallel liquidity channels that operate largely outside the regulatory assumptions underpinning the modern financial order.

Over the past decade, the consequences of these dynamics have become severe and self-reinforcing. Armed militant groups sustained by global shadow liquidity from resource theft and drug trafficking have destabilized large swaths of the Sahel. Industrial-scale scam operations in Southeast Asia and parts of Africa rely on coerced labor, embedding vulnerable populations in criminal economies that prey disproportionately on the elderly in aging industrial societies. Other multinational laundering networks sustain transnational cartels that distribute lethal products while recycling billions in illicit proceeds.

In both underregulated jurisdictions and advanced economies, the downstream effects are increasingly visible: criminalized local ecosystems, degraded infrastructure, housing market distortion, and the erosion of demographic resilience essential to long-term social stability.

If left unchecked, these illicit flows have the power to destabilize and degrade modern life at a systemic level. For this reason, network-level disruption—not merely transactional interdiction—is imperative.

Toward Networked Disruption

Regulators and enforcement professionals are beginning to grapple with the scope of the challenge. Financial institutions, insurers, manufacturers, and other exposed sectors have devoted increasing resources to understanding global financial risk, giving rise to specialized internal teams and a growing ecosystem of external advisory firms of uneven quality. Enforcement authorities have also come to rely more heavily on the emerging blockchain analytics sector, but often as a partial substitute for deeper structural investigation.

For criminal organizations and malign state actors, blockchain has proven to be a double-edged sword. While it enables near-instantaneous, low-friction value transfer across jurisdictions, the permanent recording of transactions on public ledgers creates cumulative exposure once investigators begin reconstructing networks. Advances in machine learning and artificial intelligence – as I chronicled for an October article at GNET – have further accelerated the ability to cluster, trace, and contextualize these datapoints at scale, offering meaningful advantages over traditional investigative methods.

Regulatory efforts to bring key enablers—such as stablecoins—more fully within existing compliance frameworks are a necessary step forward. But transactional visibility and downstream disruption alone are insufficient. Achieving durable, network-level impact in a way that meaningfully improves global security requires a deeper understanding of how unregulated capital forms, aggregates, and moves at its source—before it is laundered, weaponized, or embedded into resilient criminal and state-aligned illicit infrastructures.

Why Timing Capital Outflows Is Essential

Understanding why timing matters requires close examination of where unregulated capital flows originate. In an increasingly polarized global financial environment, states seeking to operate outside the dollar-denominated system—often due to sanctions or anticipation of future sanctions—have enabled parallel financial architectures to sustain economic activity.

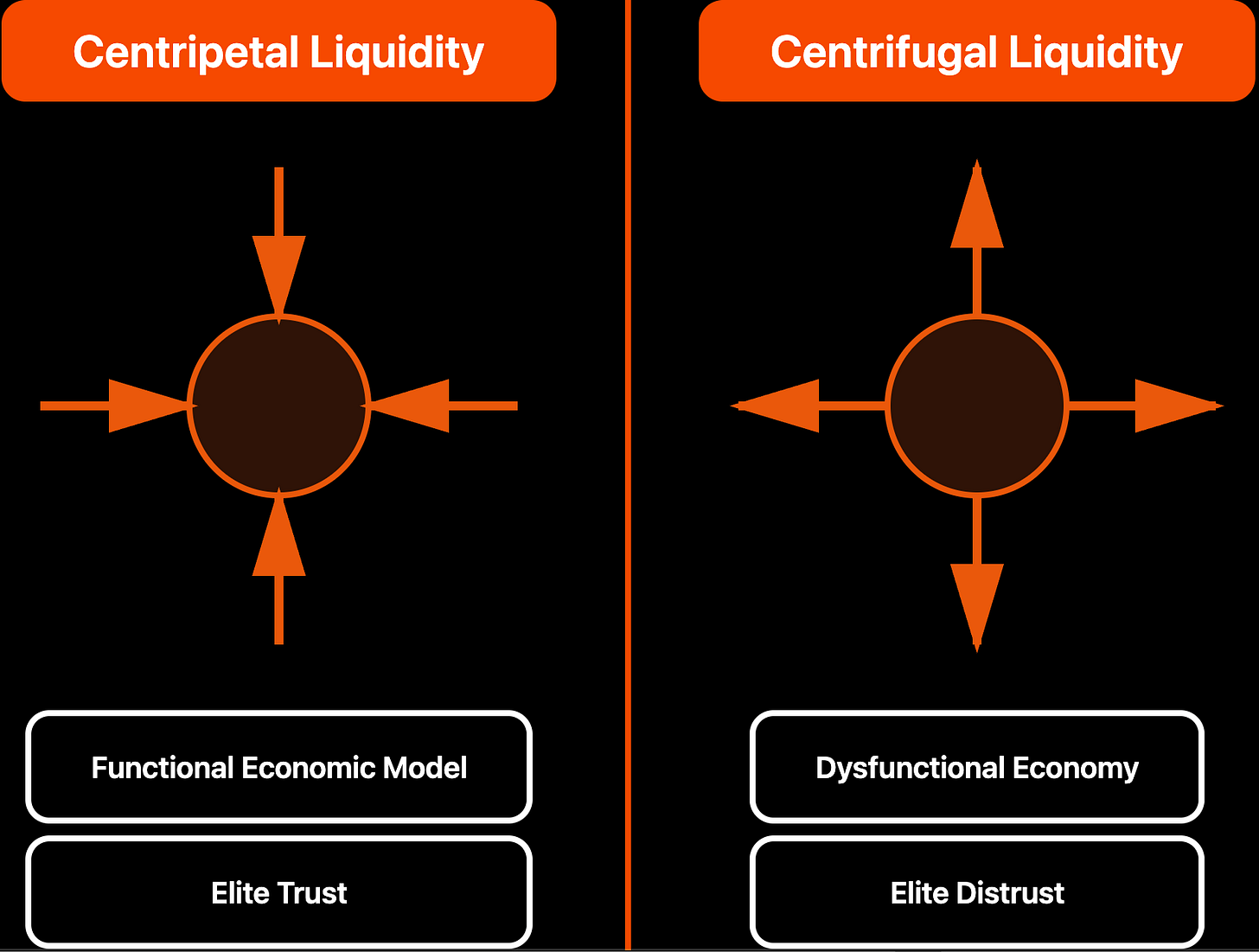

When these systems function as intended, they pull liquidity inward toward core institutions – especially central banks – reinforcing local currencies and supporting essential state functions under stress conditions such as wartime sanctions. As long as confidence holds, capital movement within these systems remains predominantly centripetal, stabilizing rather than eroding the domestic financial base.

But opacity of these parallel systems is both a feature and a fault. Because they are unaccountable by design—even to the states that authorize them—these systems enable insiders to quietly extract and offshore wealth. When confidence begins to fracture, elite incentives shift rapidly. Pressure to externalize capital compounds, transforming inward-facing financial mechanisms into outward-facing extraction channels. At this inflection point, operators increasingly seek offshore liquidity through any available means, including partnerships with transnational criminal networks and, in some cases, the financing of terrorism. When the financing of other states or proxy groups through these opaque networks becomes a state directive, the rate of elite pilfering often accelerates, as illicit capital movement is shielded by national security justifications and subjected to even less internal oversight.

Importantly, Tier 2 capacity is not unlimited. As unregulated capital outflows accelerate, intermediary networks can become congested, creating observable bottlenecks before capital fully disperses downstream. In several recent cases, unusually large pools of digital assets appear to have stalled within intermediary structures rather than being rapidly laundered onward, suggesting constraints in conversion, layering, or off-ramping capacity.

One widely reported example involves Prince Group, which has been linked in open-source reporting to the custody of a multibillion-dollar bitcoin balance. Regardless of ultimate attribution or intent, the scale and persistence of such holdings are difficult to explain by benign delay alone. More plausibly, they reflect saturation at the Tier 2 level—where capital has exited its origin environment but cannot yet be safely or efficiently absorbed into downstream structures.

Such congestion is analytically significant. It indicates that Tier 1 outflows are already stressing intermediary networks, even before full centrifugal dynamics take hold. For analysts and enforcement bodies, these stalled pools may therefore function as early warning indicators of impending cascade behavior rather than isolated anomalies.

This dynamic is already visible across multiple jurisdictions. Unregulated capital outflows from China are enabling multibillion-dollar transnational scam networks, casino-based laundering nodes, and drug trafficking organizations. Opaque outflows from Iran provide direct financial services to proxy groups and, indirectly, to terrorist organizations operating beyond Tehran’s stated strategic interests, including al-Qaeda-aligned actors in Somalia. Russia, meanwhile, relies on opaque financial channels to source physical gold and sanctioned inputs through criminal facilitators and private military companies operating abroad, sustaining its war effort under mounting external pressure.

When systemic trust in these environments deteriorates, capital outflow pressures compound. Iran’s parallel systems have already shifted into a centrifugal phase of capital flight, one likely to generate escalating downstream threats as stress persists. Russia continues to attract liquidity inward, but sustained trade contraction and reserve drawdowns increase the risk of a similar inflection. China, while still appearing stable on paper, has experienced persistent capital leakage for several years—producing some of the most severe downstream criminal and security effects observed to date.

These systems are inherently brittle. The strategic question is not whether they will fracture, but when. Once that threshold is crossed, vast pools of liquidity move rapidly through opaque channels that intersect with criminal and militant actors, producing destabilizing effects that are difficult to reverse. Understanding when these outflows are likely to accelerate—and at what scale—is therefore essential to planning any form of pre-emptive, network-level disruption of illicit liquidity systems.

A simplified diagram of centripetal vs. centrifugal liquidity flows through unregulated Tier 2 channels.

Understanding Capital Logic

In a post–Bretton Woods system, dollar-denominated capital tends to concentrate in jurisdictions that offer:

Credible protection of property rights through predictable legal and regulatory institutions

Stable, transparent, and non-punitive tax regimes

Deep, liquid, and internationally integrated financial systems

Political and currency stability sufficient to preserve real value

Credible exit optionality, allowing capital to move without arbitrary restriction or penalty

Broad-based asset appreciation that rewards passive capital over time

These conditions largely explain why, over the past fifty years, global wealth has been reinvested disproportionately into Western financial markets—particularly the United States, which combines deep capital markets with unmatched legal and currency credibility.

In highly controlled jurisdictions with adversarial or semi-adversarial relationships to Washington—such as China, Russia, and Iran—capital behavior is governed by a different logic. In these systems, jurisdictional prudence becomes a critical X-factor shaping whether capital remains onshore or seeks exit.

In such environments, capital can rationally remain domestic despite restrictive controls if two conditions hold:

The domestic economy continues to offer returns that exceed the cumulative cost and risk of outward transfer

Regime behavior remains bounded and predictable, such that capital faces managed exposure rather than sudden or arbitrary appropriation

Where these conditions are met, capital inertia is often the rational outcome—even in jurisdictions that lack many of the features typically associated with capital-attracting environments. But when these conditions go away, typically as a feature of economic downturns borne of deep structural flaws, capital takes flight, even at enormous cost to its owners. However, the adoption of cryptocurrencies, including central bank digital currencies, reduces the cost and increases the speed of capital mobility, reducing the time it takes for downstream threats to manifest.

There is no universal formula for precisely timing or quantifying Tier 1 capital outflows. What is increasingly clear, however, is that the velocity of modern unregulated finance causes downstream threat formation to accelerate rapidly once cascading dynamics are triggered. Conventional country risk frameworks have consistently misread these systems as more stable than they are by ignoring the behavior of elite capital under stress. Effective security intervention therefore depends on identifying and disrupting Tier 1 outflows before they metastasize into downstream criminal and militant activity.

A mathematical simplification

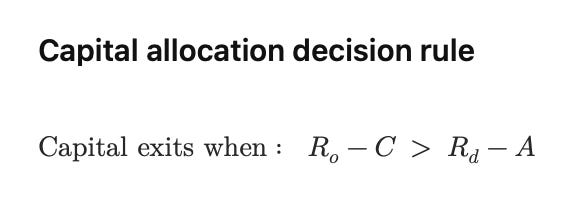

I have formalized this logic into a simple decision rule governing capital outflows from tightly controlled jurisdictions. The formulation builds on John T. Cuddington’s 1986 treatment of capital flight as a portfolio response, updated to reflect the substantially lower costs and reduced barriers to entry created by contemporary Tier 2 facilitators.

In this formulation, Rd denotes the expected return on domestic assets, adjusted for political and regime risk. This adjustment, A, captures the probability and severity of arbitrary state intervention, expropriation, capital freezes, or discretionary enforcement that reduces the effective value of onshore wealth.

Ro denotes the expected return available in offshore jurisdictions, reflecting both asset performance and institutional credibility abroad. The term C represents the cumulative cost of externalization, including capital controls, transaction and intermediary fees, time delays, enforcement exposure, and operational risk associated with moving capital across borders.

Capital remains onshore when the risk-adjusted domestic return (Rd minus A) exceeds the offshore alternative net of externalization costs (Ro minus C). Capital flight becomes the rational outcome once this inequality reverses.

Technologies that reduce transfer friction—most notably cryptocurrencies and related settlement infrastructures—operate by lowering C, thereby compressing the time between deteriorating domestic conditions and large-scale capital outflows and accelerating the emergence of downstream threats.

Bridging the siloes

One of the primary reasons these dynamics continue to be misread is that the systems responsible for monitoring finance, trade, sanctions, and security risk remain analytically siloed. Capital flight is treated as a macroeconomic concern. Trade distortions are assessed separately from illicit finance. Criminal and militant threats are examined downstream, long after the financial conditions that enable them have already taken shape.

This fragmentation obscures the timing problem at the center of modern illicit liquidity. By the time financial and/or political instability registers in conventional economic indicators—or downstream threats become visible to security services—the critical window for upstream intervention has often already closed as Tier 2 intermediaries have scaled. Capital has dispersed. Criminal and militant actors have embedded themselves into resilient networks that are costly and difficult to unwind.

Bridging these siloes is therefore not a matter of institutional reorganization, but of analytical integration. Understanding when and how Tier 1 capital begins to externalize—across financial, trade, and geopolitical domains simultaneously—is essential to disrupting Tier 2 networks before they mature and preventing downstream threats from metastasizing at scale.

Conclusion

Modern illicit liquidity systems move faster than the frameworks built to monitor them. As capital mobility accelerates and parallel financial architectures grow more opaque, downstream threats will continue to emerge faster than reactive enforcement can contain them.

The central challenge is no longer attribution after the fact, but anticipation. Identifying when Tier 1 capital begins to externalize—how quickly it moves, where it encounters friction, and when intermediary capacity begins to saturate—has become the decisive variable in preventing the downstream consolidation of criminal and militant power.

Meeting this challenge requires analytical integration across finance, trade, sanctions, and security domains. Without that integration, institutions will continue to misread stability, intervene too late, and confront threats only after they have embedded themselves into resilient networks.