From Resilience to Extraction: How Iran’s Shadow Financial Systems Are Hollowing Out the State

A Three-Tier Model of Sanctions Resilience and Capital Flight

Protests have erupted across multiple Iranian cities, with demonstrators chanting “death to the dictator.” Such unrest is not new: major waves occurred in 2009, 2017–2018, and 2022–2023. What appears different in the current cycle is its socioeconomic base. Reporting suggests mobilization began in poorer and working-class communities that have historically provided key regime support, before extending into more familiar youth dissident ranks. This pattern points to economic stress as the primary catalyst for the current wave of unrest.

Iran’s economic deterioration has sharpened the underlying drivers of these ongoing protests. Inflation and currency depreciation have eroded purchasing power, while chronic underinvestment has compounded basic-service failures, including acute water stress. With limited fiscal room to stabilize living conditions at scale, the state has increasingly relied on coercive containment—reinforcing incentives for households and elites alike to externalize wealth.

Iran’s accelerating economic crisis is not solely the product of sanctions or mismanagement. It is increasingly driven by capital flight embedded within the same networks initially developed to foster state resilience—networks that now operate beyond effective control. Under pressure, opaque networks built for sanctions resilience and regional power projection now function as conduits for capital flight.

A siege economy overseen by a multidimensional security actor

Iran is among the world’s most heavily sanctioned states, and has been for nearly five decades, severely constraining its access to formal financial systems and conventional trade finance. To function, the Iranian state and economy rely on a fragmented but resilient ecosystem of informal, semi-formal, and illicit channels to sustain trade, preserve value, and maintain currency stability.

Within this environment, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC)—a multiservice institution with paramilitary, intelligence, and economic roles—has emerged as a central coordinating actor. While not the sole driver of sanctions evasion, the IRGC plays a critical role in overseeing and stabilizing the networks that enable Iran to operate under prolonged economic pressure. The Quds Force, IRGC’s elite external operations arm, oversees these foreign facing networks.

These networks include shadow tanker fleets moving discounted Iranian crude to global markets, procurement channels sourcing dual-use components for domestic weapons production, and trade and logistics firms facilitating the movement of high-value commodities such as physical gold, and informal financial institutions. In several cases, Iranian proxy organizations participate directly in these systems, often in exchange for financing, logistical support, or political backing facilitated by the IRGC.

For example, Hezbollah-linked networks in Venezuela have participated in gold smuggling operations connected to Venezuelan supply chains, while Houthi-linked facilitators have played roles in brokering oil shipments to independent refiners in China. Across these pathways, IRGC-affiliated actors frequently provide coordination, protection, or logistical oversight, giving them visibility into — and influence over — critical flows of capital and goods.

By anchoring these networks, the Quds Force does not merely facilitate sanctions evasion; it effectively underwrites the movement of value into and out of the Iranian economy. This role has helped sustain economic functionality under extreme external pressure – driving export revenue and necessary imports while arming regional proxies – but it has also enabled significant capital outflows. In this sense, the Quds Force operates not only as a military or intelligence institution, but as a central node in Iran’s siege-economy infrastructure — one that governs access, risk, and continuity across otherwise fragmented financial and trade networks. Because these networks operate through opaque and compartmentalized channels, and because the IRGC ultimately answers only to the Supreme Leader - an 86-year-old man who frequently avoids the spotlight amid health speculations - they are structurally vulnerable to elite capture and internal rent-seeking.

Within Iran, the broader IRGC organization has consolidated control over much of the domestic economy. Companies such as Khatam al-Anbiya, an IRGC-linked engineering firm, have vast interests across the Iranian economy ranging from fuels and hydrocarbons to agriculture, mining, real estate, and infrastructure. IRGC functionaries have even intervened to prevent a major tech company from going public last year, presumably as a means of managing control over it. Major defense contractors such as Shahed Aviation – responsible for Iran’s Shahed drone program – also fall under the control of the IRGC’s vast portfolio of domestic assets.

The IRGC also captures a large share of state spending through defense and infrastructure procurement. Estimates suggest it receives roughly 34% of total military expenditure, which rose sharply in 2025 (to an estimated $23.1 billion). Given the IRGC’s influence over key suppliers and contractors, a significant portion of this spending flows into opaque channels it controls.

Taken together, these dynamics form the architecture of a vertically integrated siege economy. The broader IRGC consolidates and captures liquidity domestically through control of procurement, infrastructure, defense production, and budgetary flows, while the Quds Force manages the external channels that move value across borders, absorb sanctions risk, and interface with deniable networks. Under conditions of sustained pressure, this division of labor preserves regime functionality but also facilitates capital flight, as assets accumulated within the domestic system are routed outward through opaque, compartmentalized pathways beyond effective oversight.

Stress Test Conditions

Iran’s economic system is undergoing a sustained stress test shaped by three converging pressures: intensifying sanctions, escalating regional conflict with Israel, and accelerating capital flight. The latter of these has been enabled by informal financial mechanisms and weak regulatory enforcement, and comes in response to the former two. Together, these forces are pushing the country beyond episodic economic strain and toward a deeper crisis of economic governance, resulting in widespread capital flight and the erosion of monetary stability.

Regional Conflict, Military Costs, and Collapsing Revenue

The financial burden of Iran’s expanding regional confrontation has grown sharply. Analysts estimate that the country’s direct and indirect costs from its recent 12-day conflict with Israel alone were $24 - $35 billion, a figure that does not account for the ongoing and open-ended costs of proxy warfare across Lebanon, Iraq, Syria, and Yemen. Even conservatively assessed, this level of expenditure represents a meaningful share of national output—exceeding 6% of GDP—at a time when Iran’s economy is already contracting under sanctions pressure.

These military outlays are colliding with mounting stress on the state’s primary revenue base. Petroleum and mineral fuel exports—historically comprising over 30% of government revenue, and some 80% of export earnings—have come under increasing strain. Demand for Iranian crude has softened as Chinese buyers grow more cautious amid escalating foreign pressure and enforcement risk. Moreover, the discounted oil market became more saturated after 2022 as sanctioned Russian crude expanded supply, compressing margins.

Compounding these pressures, recent seizures of oil tankers linked to sanctioned networks—particularly off the Venezuelan coast—have cast doubt on the long-term viability of shadow tanker fleets. While some speculate that Chinese buyers will purchase Iranian crude to make up for their recently disrupted Venezuelan supplies, this ongoing enforcement against shadow tanker fleets could further impact these shipments. With a Russian-flagged tanker seized by US forces in the Atlantic on January 7, ship owners and crews may become unwilling to transport sanctioned oil supplies, especially amid questions of whether Chinese and Russian state-owned and shell company insurers will cover losses from vessel seizures. These developments raise concerns that Iran could face a sharp disruption in export capacity as early as 2026, undermining one of the last remaining pillars of fiscal stability.

Weaponized Fintech: Digitalizing the Siege Economy

Under prolonged sanctions, Iran emerged as an early adopter of crypto and alternative digital payment systems designed to bypass formal banking channels. What initially functioned as a tool of sanctions resilience has increasingly devolved into a dual-use financial infrastructure—supporting both state procurement and large-scale capital outflows. While crypto does not replace trade-based channels in volume, it compresses settlement time, reduces visibility, and lowers exit friction for elite capital flight.

Iran’s largest domestic exchange, Nobitex, illustrates this dynamic. Investigations by blockchain analytics firms have linked the platform to wallet clusters and transaction patterns consistent with IRGC-aligned financial activity, suggesting that it functions not merely as a commercial exchange, but as a critical node within Iran’s cross-border sanctions-evasion architecture. These channels have reportedly been used to facilitate procurement of dual-use components for Iran’s drone and weapons programs, particularly where conventional trade finance is unavailable.

At the same time, this infrastructure has facilitated massive capital flight. Transaction data indicate that crypto outflows surged sharply during periods of heightened geopolitical tension—including a reported 150 percent spike in mid-2025 amid escalating confrontation with Israel—highlighting how digital financial tools simultaneously enhance regime resilience and accelerate elite asset externalization.

In this sense, fintech is the digital extension of Iran’s siege economy—one that further erodes state visibility, weakens monetary control, and compresses the boundary between sanctions evasion and private capital flight. As pressure on physical export channels has intensified, Iran’s reliance on non-physical and digitally mediated settlement mechanisms has increased in parallel. Without regulatory accountability, these digital channels give elites an unprecedented opportunity to hollow out the Iranian economy while their assets come under stress.

Capital Flight and Monetary Erosion

At the same time, capital flight has accelerated through informal channels operating beyond effective state oversight. In 2024, Iranian capital outflows reached $20.7 billion, triple what they were in 2020: estimates for 2025 could place these at $36 billion, roughly 10% of GDP. These movements reflect not only popular distrust in the rial, but also growing elite efforts to externalize wealth amid political uncertainty, inflation, and deteriorating public services. Iran’s widespread adoption of crypto has become a dual-use enabler, allowing the regime to purchase critical components outside sanctions controls, but also permitting wealth to flow out of the country with minimal restriction – all through loosely regulated IRGC-managed channels.

The monetary and social consequences have been severe. Central bank assets have continued to decline as the government increasingly relies on monetary expansion to cover rising debts and budget shortfalls created by falling export revenue. This dynamic has accelerated the depreciation of the rial, fueled persistent inflation, and eroded household purchasing power. Rising living costs—combined with structural stresses such as water mismanagement and infrastructure decay—have triggered repeated protest waves, further reinforcing elite incentives to offshore capital rather than reinvest domestically.

A Governance Crisis, Not a Liquidity Shock

What is emerging is not a temporary liquidity squeeze, but a deeper crisis of financial governance. The Iranian state increasingly struggles to manage the very systems it once used to project power, enforce political control, and buffer external pressure. Informal mechanisms that once enhanced resilience—shadow trade, opaque financial channels, and coercive enforcement—are now amplifying instability by enabling capital flight, weakening fiscal discipline, and reducing the state’s visibility over its own economic base.

Under these stress-test conditions, Iran’s economic challenge is no longer simply sanctions survival. It is the erosion of the state’s capacity to govern liquidity, allocate resources, and retain elite confidence—an imbalance that becomes progressively harder to correct the longer it persists.

Three-Tier Financial Architecture

Understanding Iran’s capital flight dynamics requires moving beyond linear models that separate state finance, sanctions evasion, and proxy activity into discrete domains. In practice, these functions are integrated through a three-tier financial architecture that deliberately separates control, mobility, and utilization of capital. This structure has enhanced Iran’s resilience under sanctions, but it has also accelerated elite capital flight. These factors externalize financial risk onto regional and global markets, and security risk into the broader global community.

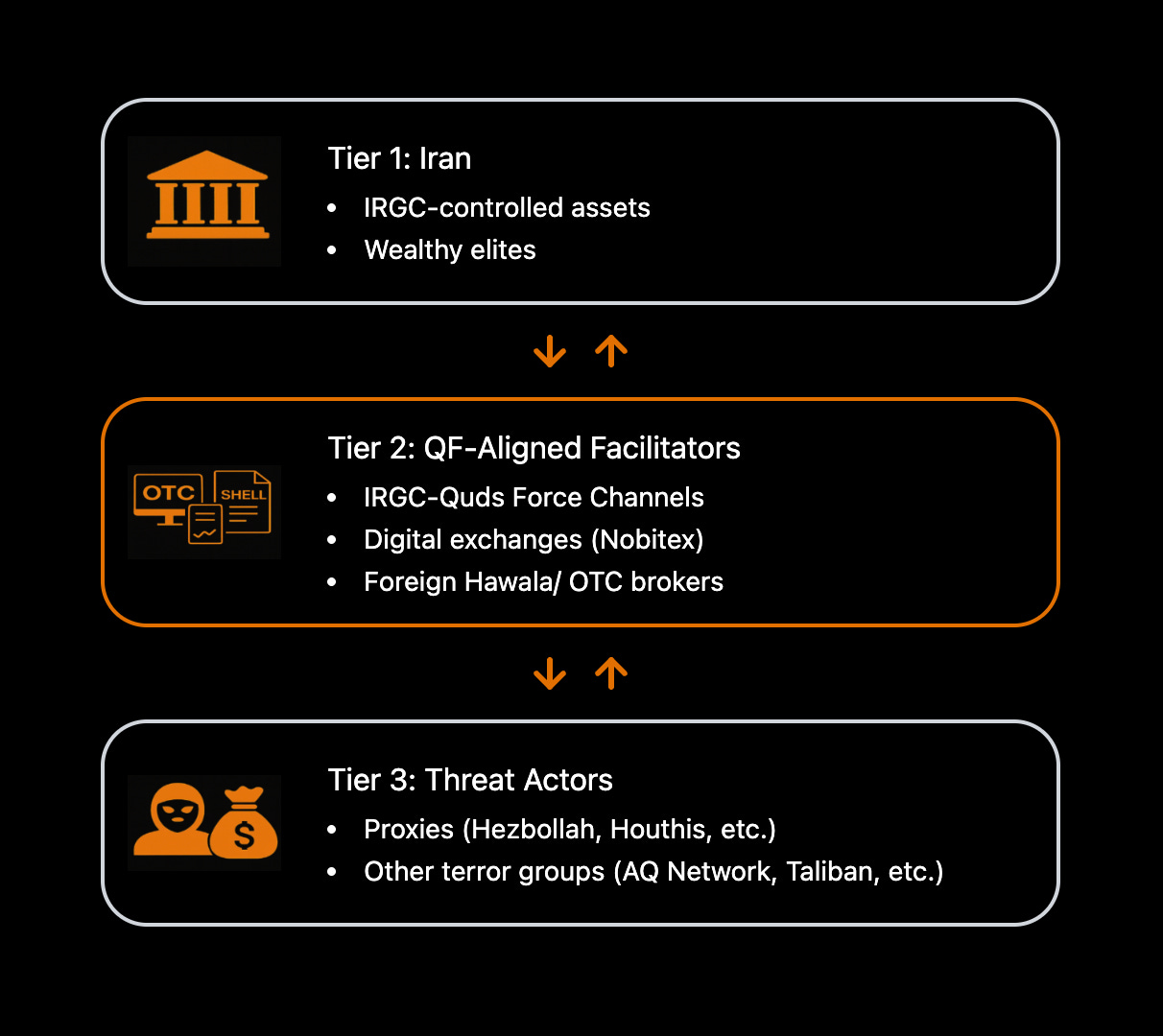

A model of the three-tiered framework applied to Iran

Tier 1: Iran

At the apex of this system sits Tier 1, composed of state and private institutions, politically connected elites, and intermediaries who generate, authorize, or appropriate economic value. This tier includes state-linked corporations, import–export firms, and wealthy individuals with preferential access to foreign exchange, trade licenses, and protected commercial channels – all increasingly under the influence of the broader IRGC organization. Under sustained sanctions pressure, Tier 1 actors have increasingly prioritized wealth preservation over domestic reinvestment. Rather than functioning as anchors of economic stability, many now behave as rational extractors, externalizing capital while maintaining nominal alignment with the system.

Loosely regulated and opaque by design, this tier leaks much more liquidity out of the country than is sustainable under current stress conditions. This leakage creates downstream threats at the Tier 3 level. Importantly, this tier does not move capital efficiently on its own. It depends on Tier 2 intermediaries capable of operating in opaque environments where formal institutions cannot function.

Tier 2: IRGC-Quds Force-linked Networks

That intermediary role is fulfilled by Tier 2, the facilitation and mobility layer. This tier converts domestically constrained or politically sensitive value into mobile, sanctions-resilient capital. It encompasses logistics firms, ports, trade companies, crypto exchanges, and financial intermediaries that operate at the boundary between legality and informality. Within this layer, the IRGC-Quds Force plays a central structural role. Rather than acting as a universal operator, it functions as a guarantor of enforcement, protection, and continuity. Through its influence over logistics corridors, customs chokepoints, and security arrangements, it underwrites the reliability of transactions that would otherwise be too risky to sustain. As a result, Tier 2 infrastructure processes state funds, elite capital, and proxy-generated revenue through the same channels, blurring distinctions that once separated these streams.

Although not the sole agent, the Quds Force serves as the operational backbone of this layer, underwriting vast networks linked to domestic institutions such as logistics and trading firms as well as exchanges such as Nobitex. This shadow banking system extends to foreign brokers in places such as the Persian Gulf and Hong Kong: some of these run over the counter (OTC) crypto trading desks and many more are nodes in vast informal hawala networks – all operating outside formal and regulated banking channels.

Tier 3: Proxies and other downstream threats

At the downstream end of the architecture sits Tier 3, composed of Iran’s proxies and other threat actors. Often mischaracterized as passive recipients of state financing, many of these groups now operate as semi-autonomous financial entities, enabled by Tier 2 facilitators. Through trade, logistics, smuggling, construction, and real estate activity, they circulate capital across regional markets and embed themselves within local commercial ecosystems.

Several proxies have diversified beyond reliance on Tehran’s fiscal health, reducing exposure to Iran’s domestic instability while increasing financial independence from the state. Examples include the Houthis’ use of Southeast Asia’s gray finance networks and Iraqi militias’ manipulation of local cash economies. Proxy revenues, however, are not fully externalized. Capital is frequently cycled back through Tier 2 infrastructure, where IRGC-linked facilitators provide conversion, protection, and partial normalization under state cover. Once processed, these funds are redeployed into longer-term assets, particularly high-end real estate and commercial investments in Iraq and the Gulf. This circular flow collapses traditional distinctions between state finance, proxy finance, and private capital flight.

The risks extend beyond Iranian proxies themselves. Tier 3 networks are opaque by design and difficult to control, generating spillover effects. The Houthis maintain ties with Somalia’s al-Shabaab, which sells illegally exported charcoal through Iranian-linked ports and logistics firms. Al-Qaeda retains a residual presence inside Iran under nominal state protection, while the Taliban launder funds through Iranian Tier 2 channels. In one example, an Iranian official in the pharmaceutical industry warned that underground exports of Iranian medicine to Taliban-controlled Afghanistan could lead to critical shortages at home.

Together, these linkages illustrate how Tier 3 actors increasingly function as connective tissue between sanctioned states and transnational militant economies, amplifying risk well beyond Tehran’s nominal strategic intent.

Implications: Why the three-tiered model matters

This three-tier structure explains why Iran’s economic stress manifests not as sudden collapse, but as progressive governance erosion:

• Tier 1 extracts value faster than it reinvests.

• Tier 2 optimizes mobility rather than oversight.

• Tier 3 diversifies and entrenches capital beyond the state’s reach.

The architecture that once enhanced sanctions resilience now amplifies capital flight, reduces monetary visibility, and exports financial and security risk into neighboring markets. Over time, the state shifts from governor of liquidity to one participant among many—struggling to reassert control over systems it helped build but can no longer fully supervise.

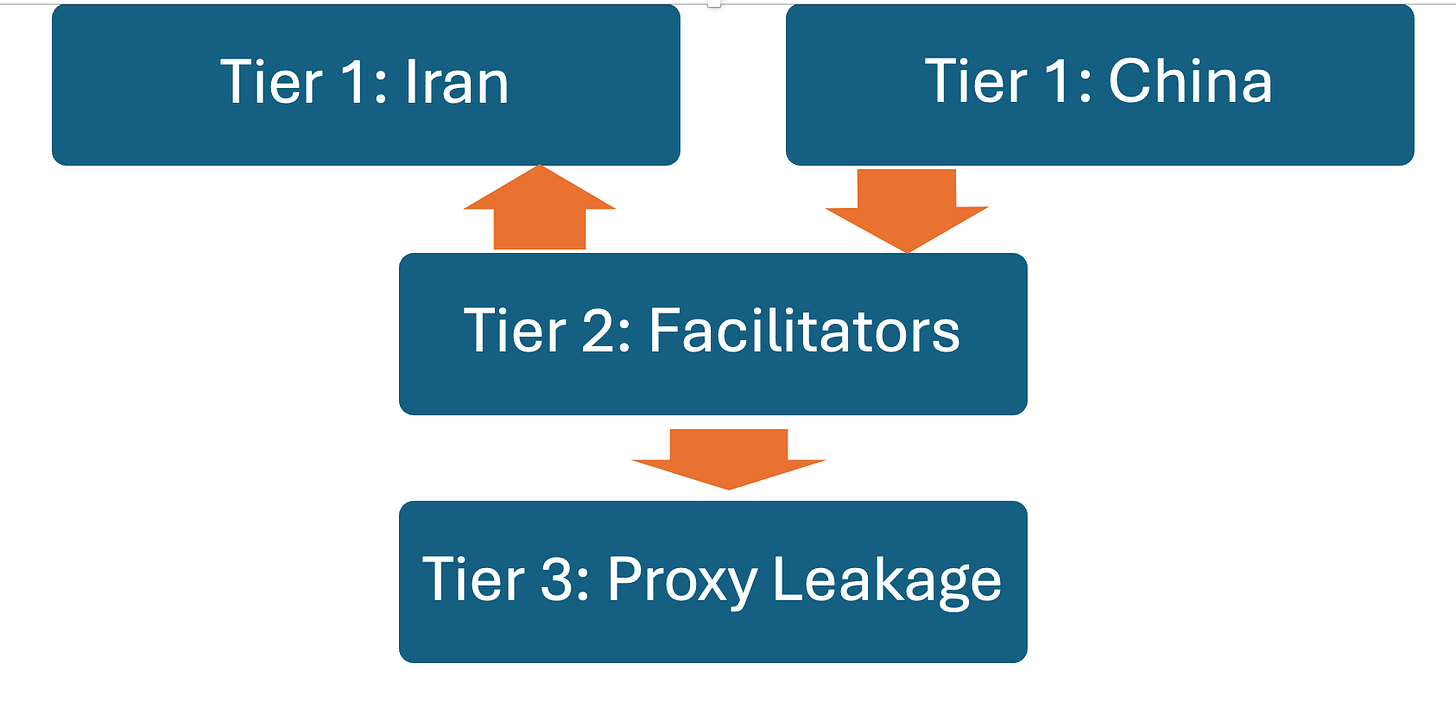

China’s role as the primary buyer of smuggled Iranian oil extends this architecture beyond Iran’s control space. Revenue routed through Tier 2 facilitators returns to state-linked channels, with evidence that portions leak into proxy finance. If Houthi-linked oil sales and the subsequent movement of at least $39 million through the Chinese-language Huione platform in Cambodia are connected to Iranian oil revenue streams, they suggest that Tier 2 infrastructure enables not only cross-tier proxy funding but also intra-tier diversion of state-linked proceeds.

Crucially, this infrastructure is not exclusively used by Iranian proxies. The same Tier 2 channels that facilitate proxy finance also provide liquidity, laundering, and settlement pathways for non-proxy militant actors operating in proximity to Iranian networks. Taliban-linked actors have laundered funds through Iranian facilitation channels, while residual al-Qaeda networks have exploited Iran-based logistics, transit, and financial intermediaries under varying degrees of state tolerance. These interactions need not reflect unified strategic intent to generate risk: they emerge from the availability of deniable, sanctions-resilient infrastructure operating beyond effective oversight.

The cumulative effect is the emergence of shadow financial systems that are increasingly more resilient than the state structures that enabled them. These networks adapt quickly, move capital efficiently, and operate across jurisdictions with minimal accountability—shaping regional security dynamics regardless of regime outcomes and, in some cases, enabling coercive or violent activity well beyond Iran’s nominal strategic priorities.

A model of how Tier 1 Iranian oil smuggling indirectly facilitates Tier 3 proxy funding through Tier 2 facilitators.

Conclusion

Capital outflows are not the sole cause of Iran’s economic crisis, but they serve as a critical accelerant. By weakening monetary stability, empowering unaccountable actors, and eroding institutional authority, they deepen systemic fragility. What remains is an economy increasingly governed by survival logic rather than policy, where financial power resides not within the state but within the shadow structures that have grown around it.