This Time is Different: Iran's New Reformist President

The election of a new reformist Iranian president has earned skepticism and scorn among much of the international press. Historical context suggests they are missing the point.

Masoud Pezeshkian’s inauguration was quickly followed by another event that threatens to escalate rising tension in the Middle East. Image source

On July 31, an explosion inside a heavily guarded Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) guest house in Tehran killed Hamas political leader Ismael Haniyeh, along with his bodyguard. Reports indicate that agents – presumed acting on behalf of Israel – smuggled an explosive device into the guest house weeks prior. Haniyeh – a key negotiator in ongoing multilateral ceasefire talks between Hamas and Israel – was in Tehran attending the inauguration of newly-elected Iranian president Masoud Pezeshkian.

This incident is the latest in a series of incidents threatening to escalate the ongoing conflict across much of the Middle East. As tensions continue to mount, Pezeshkian – a reformist – represents the possibility that a negotiated settlement may be reached before the situation spirals out of control. However, as with previous Iranian reformist administrations, there are also many possibilities for derailment.

Skeptics are missing the bigger picture

Most Western observers had little positive to say about the July 6 election of Masoud Pezeskhian, a 69-year-old former surgeon-turned-reformist presidential candidate. The Hill ran the headline "Iran's new president is no moderate," noting the lack of fairness in Iran's electoral process and Perzeshkian's admitted loyalty to Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei. Similarly, a spokesperson for the US State Department declared that "The elections in Iran were not free or fair. As a result, many Iranians chose not to participate at all…We have no expectation these elections will lead to fundamental change in Iran's direction or more respect for the human rights of its citizens."

These assessments are not wrong, but they miss the bigger picture. Yes, Iran's elections are notoriously unfair, and the country's human rights record is too abysmal for any president to address during his time in office fundamentally. Indeed, no reformist candidate has ever been elected to the Iranian presidency without the implicit backing of the Supreme Leader, making any chance of reform incremental, at best. But that's the point. The Supreme Leader has even interfered in previous elections to pave the way for reformist candidates, such as in 2017 when he barred notorious hardliner and former president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad from running against reformist president Hassan Rouhani. This time, it's clear the regime has some use for a reformist presidency at this perilous moment in the country's history.

The Supreme Leader's tacit backing of reformists typically signals the regime's desire for a policy shift, usually toward the outside world. Although a reformist president does not signal the kind of complete change the West would like to see in Iran, it can and has led to breakthroughs in US-Iranian relations. Iranian presidents are technically subordinate to the Supreme Leader. Still, the Supreme Leader typically gives presidents broad authority to set their policy agenda, only exercising veto powers through the Guardian Council when deemed necessary. In short, the election of a reformist president means that the regime sees him as the right man for his time and place. With tensions in the Middle East now higher than ever before, the election of a reformist likely signals Iran's willingness to come to the bargaining table with the West. Pezeshkian's recent vow to lift Western sanctions against the country makes this desire abundantly clear.

Some may argue that the Iranian regime permitted the election of a reformist administration for purely domestic reasons with little hope for a significant change in foreign policy. Regarding domestic politics, there is some truth to these claims. Indeed, Iran's poor economic performance and mass protests in response to widespread human rights abuses under Raisi signaled the need for change domestically. Pezeshkian's Azeri heritage may also help the regime ease rising ethnic tensions. Skeptics of the newly minted administration also point to Pezeshkian's meetings with senior leaders from Hezbollah, Hamas, and the Houthis, as well as his praise for Russia and China, as indicators that the new president lacks the desire to engage with the West meaningfully.

However, the painting of the new administration as unopen to a shift in foreign policy is not entirely fair, given that Pezeshkian entered office at a time unlike any of his reformist forebearers. Iran is effectively locked in a multifaceted regional proxy war, and the regime is not about to turn its back on allies at such a dangerous moment. However, by bringing Iran's allies close, the new president demonstrates that he may hold the keys to a comprehensive deal for the region.

A photo of the IRGC guesthouse following Haniyeh’s July 31 assassination. Image source

The failure of past reformists

Skeptics note that Pezeshkian is not the first Iranian reformist president and that others have failed to improve their country's relations with the West fundamentally. There is some truth to this, but it is far from the whole story.

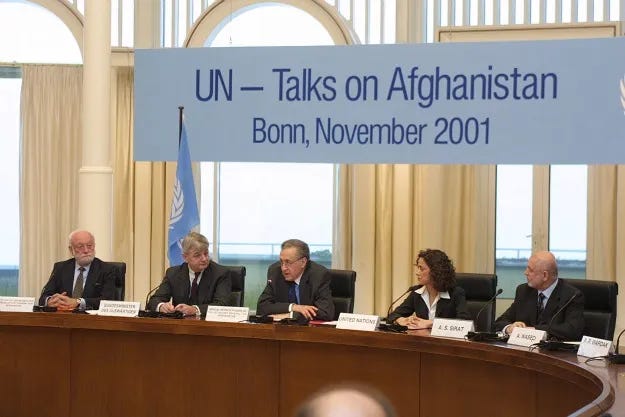

The 1997 Iranian presidential election delivered the reformist administration of Mohammad Khatami. The administration moved the country toward reconciliation with the West in some key ways, and at a moment of heightened tensions after the 1996 bombing of a residential apartment block in Khobar Saudi Arabia by Iranian proxy, Hezbollah al-Hijaz. Khatami initiated a "dialogue of civilizations" upon reaching office in 1997, prompting President Bill Clinton to send a letter to the Iranian President, the first direct communication between the two countries' leaders since the 1979 overthrow of the Shah and the subsequent Iran Hostage Crisis. Following the events of 9/11, Iran joined the long list of countries that condemned the attacks and offered condolences to Washington. In 2002, Iran entered into high-level talks with US officials in Bonn, Germany, to discuss forming a new Afghan government and ousting their mutual enemy, the Taliban. Such talks were also a first since 1979.

Although Iran had agreed to cooperate with the United States in matters related to Afghanistan, the Bush administration soon sidelined the regime amid the War on Terror. President Bush's "axis of evil" speech occurred some 11 months before the Bonn agreement and relations between the US and Iran remained cold after the former's 2003 invasion of Iraq, with the White House hitting Tehran with additional sanctions in 2004. Although Khatami's time in office remained generally conciliatory until its end in 2005 – the president even shook hands with Israeli President Moshe Katsav at the 2005 funeral of Pope John Paul II – the moment for meaningful reconciliation with Washington was lost. In 2004, US talks with Iran over Iraqi security accomplished little. Moreover, the 2005 Iranian election delivered the hardline presidency of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, during whose tenure Iran greatly expanded its influence in Iraq and across the Middle East through various proxy groups. In this way, the opportunities for rapprochement presented during the Khatami years were mainly lost to diverging interests between Washington and Tehran.

In 2013, reformist candidate Hasan Rouhani won the presidency to widespread international praise, with Time Magazine naming him one of its 100 most influential people that year. Rouhani's most important foreign policy achievement was reaching a landmark nuclear deal with the Obama administration in 2015. However, President Donald Trump heavily criticized the deal during his 2016 campaign and pulled out of it entirely in 2018. Without getting political, it is safe to say that Washington's interests shifted, thus also rendering Rouhani's efforts at reconciliation moot.

Conservative hardliner Ibrahim Raisi replaced Rouhani as president following the 2021 election. US-Iranian tensions reached new heights under his tenure amid the war in Gaza and a flareup of Iranian proxy activity across the Middle East. With Raisi's death in May and his elected successor now in office, the mutual interests of Tehran and Washington are now more aligned than during previous reformist administrations, when the stakes were much lower.

The Bonn talks, which commenced briefly after the 9/11 attacks, were the first high-level official meetings between US and Iranian representatives since 1979. Image source

President Ibrahim Raisi’s death in a May 19 helicopter crash in northwest Iran resulted in the snap election that ultimately brought about Pezeshkian’s presidency. Image source

This time is different

Current tensions between Israel and Iran represent a clear and present danger of drawing the US into an intense regional conflict, making the stakes much higher than ever. Washington's top policymakers continually call for de-escalation, and there is generally a consensus in this regard among unelected officials and politicians in both parties. This bipartisan consensus is even apparent between both hopefuls in the 2024 US presidential election, with Vice President Harris calling for de-escalation and former President Trump admitting in 2019 that he did not want war with Iran.

Although Trump's rhetoric on Iran remains consistently intense, the former president's stance on all-out war has not likely changed in the past five years, given the persistent risks such a prospect poses to American interests and those of its partners. Moreover, President Biden's recent pledge to help Israel counter the looming Iranian attack in response to Haniyeh's killing but not to support Israel should it seek to escalate the situation underlines the persistent fear of war in Washington. I've outlined many of the risks behind these fears in previous articles.

The threat of an all-out war with Israel and the US also poses significant and potentially existential risks to the Iranian regime. With neither Washington nor Tehran wanting to engage in a war of such magnitude, the interests of both countries are aligned more significantly than they have been since 1979. However, the threat of escalatory actions looms large over both countries, be it from Israel or one of Iran's proxies.

Just as Washington does not dictate Israel's actions, Tehran does not exercise complete control over its many regional proxies. If the two sides are to avoid a conflict that neither wants, they will likely need to work through diplomatic backchannels that include their regional partners. Although daunting, Tehran just signaled a willingness to engage by anointing a reformist candidate in its recent snap presidential election. For the sake of global security, let's hope this time is different.