China’s Gray Zone Syndicates – Part I: Criminal Convergence and Strategic Ambiguity in the Global Shadow Economy

How Chinese-linked criminal networks blur the lines between state strategy and illicit finance—reshaping global power through deniable influence, shadow banking, and transnational crime.

Yes, I asked ChatGPT to make me a GTA-themed cover image.

When most people think of China’s role in the global economy, they picture vast container ships, massive port infrastructure, and sprawling industrial zones. That’s accurate—but it’s not the whole story. Beneath the surface of legal trade flows exists a shadow economy: sprawling, loosely regulated, and increasingly strategic.

This is the realm of China’s gray zone strategy—the space between peace and conflict, legality and criminality. In this domain, Chinese transnational crime networks and illicit financial systems quietly advance Beijing’s geopolitical interests. These operations—ranging from online gambling syndicates to crypto laundering rings—often operate independently. Yet they frequently intersect with state-linked business interests or serve strategic ends, especially in Southeast Asia, Africa, and parts of the West.

This convergence of organized crime, illicit finance, and covert influence is no accident. It forms a plausibly deniable architecture of power—a parallel system that moves weapons, people, and digital assets while supporting China’s strategic ambitions and shielding it from direct accountability. Understanding this shadow infrastructure is essential to grasping the future of global competition and statecraft in an era defined by blurred lines and contested rules. Although other countries have credible accusations of ties to criminal rings operating outside their borders, China’s are distinct in scale and integration with state interests, such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Most of Chinese criminal syndicates operate independently. But when the moment is right, the Chinese state can and does lean on them—subtly or forcefully—to advance its goals without attribution, and often without consequence. To be clear: most of these actors are not agents directly working on behalf of Beijing (although some allegedly are), but that the system in which they operate creates space for strategic alignment and informal state benefit—a hallmark of gray zone dynamics.

What results is a decentralized, plausibly deniable financial architecture that enables Beijing’s global ambitions—not by command, but through complex relationships involving a mix of financial incentives and coercion.

Dual-Use Dynamics – Crime as Opportunity

All Chinese-linked criminal networks operating globally exist for one primary reason: profit. From online gambling rings in Southeast Asia to smuggling routes in Africa and cartel money laundering in the Americas, these groups are driven by self-interest and economic opportunity. But their operations increasingly generate strategic spillover for Beijing.

These ecosystems corrode institutions, overwhelm enforcement capacity, and destabilize fragile states. In Cambodia and Laos, Chinese-run casino compounds and scam centers have fueled trafficking, corruption, and political capture—often embedded in Belt and Road-aligned infrastructure projects. In some cases, these ventures are associated with state-linked businessmen, raising questions about their role as informal instruments of Chinese influence. Although other countries like Russia leverage their overseas crime syndicates to help meet state goals, China’s unique blend of gray finance, state-aligned enterprise, diplomatic cover, and the scale of its investment stands out.

The digital dimension is just as consequential. These criminal networks rely heavily on over-the-counter (OTC) crypto brokers, stablecoins like Tether, and platforms like Huione to move billions outside the reach of global regulators. These tools enable real-time capital mobility, payment anonymity, and sanction-resistant value transfer. Crypto is not just a laundering mechanism—it’s a core pillar of a parallel financial infrastructure that serves both illicit actors and, at times, broader Chinese interests.

In parallel, these same networks extend China’s informal reach into diaspora communities. In Canada, Australia, and the U.S., loosely affiliated actors have engaged in surveillance, harassment, and coercion of dissidents, often in tandem with Chinese consular or United Front-linked operations. These networks also help generate untaxed capital, entrench Chinese business interests, and build parallel financial infrastructures that operate well outside the purview of global regulators.

This is not a top-down operation. It’s a decentralized ecosystem—where illicit actors, shadow financiers, and state-linked intermediaries often find alignment. What emerges is a deniable architecture of power and profit—adaptable, resilient, and increasingly strategic.

US law enforcement recently sanctioned Cambodia-based Huione Pay in connection with terrorist financing and money laundering. The company’s primary focus was its regional Chinese criminal clientele. Image source

Selective Enforcement – Rule of Law as a Dial, Not a Switch

China’s approach to transnational crime is not uniformly applied—it’s strategic. Domestically, Beijing aggressively prosecutes crimes like online gambling, crypto fraud, and large-scale scamming, particularly when they risk domestic unrest or reputational fallout. Abroad, however, enforcement becomes far more selective. Crimes committed by Chinese nationals in foreign jurisdictions—especially in Southeast Asia—often draw inconsistent responses depending on the political and strategic context.

Cambodia offers a clear case in point. Chinese-run gambling and scam operations have flourished in cities like Sihanoukville, despite Beijing’s sweeping 2020 domestic ban on online gambling. While China has extradited hundreds of suspects from Cambodia—including a 2024 operation that saw over 680 nationals repatriated for fraud and illegal gambling—it has shown remarkable tolerance for larger, well-connected networks. Notably, She Zhijiang, a Chinese-born tycoon who built a regional gambling empire, operated for years despite being wanted by Chinese authorities since 2014. A self-professed Chinese spy, his eventual arrest in Thailand came only after allegations that he had defied Chinese intelligence demands—suggesting political selectivity in enforcement.

This pattern reflects a deeper logic: crackdowns at home protect social stability, while tolerance abroad enables capital outflows, influence-building, and deniable engagement in unstable environments. Sometimes mass arrests are politically expedient, especially when the criminals target victims in Mainland China of create diplomatic fallout abroad1. By regularly seeking extraditions of known criminals and prosecuting them, the Chinese state state takes a very public stance against overseas crime. However, it apparently tolerates some individuals more than others—a strategic gray zone posture, not explicit policy. In this way, Chinese law enforcement functions less like a binary switch and more like a dial—tightened or relaxed depending on what serves China’s national interest.

Having lived in China for a significant portion of my adult life, I can say the dial metaphor applies just as well to the domestic context. Laws are not fixed boundaries; they are instruments, applied flexibly to manage dissent, control capital, and preserve state authority. Internationally, this same model has been quietly exported—not as a formal doctrine, but as a political habit. What emerges is a form of rule by man, not rule by law—adapted to local environments, but unmistakably recognizable to anyone who has seen how the system works at home.

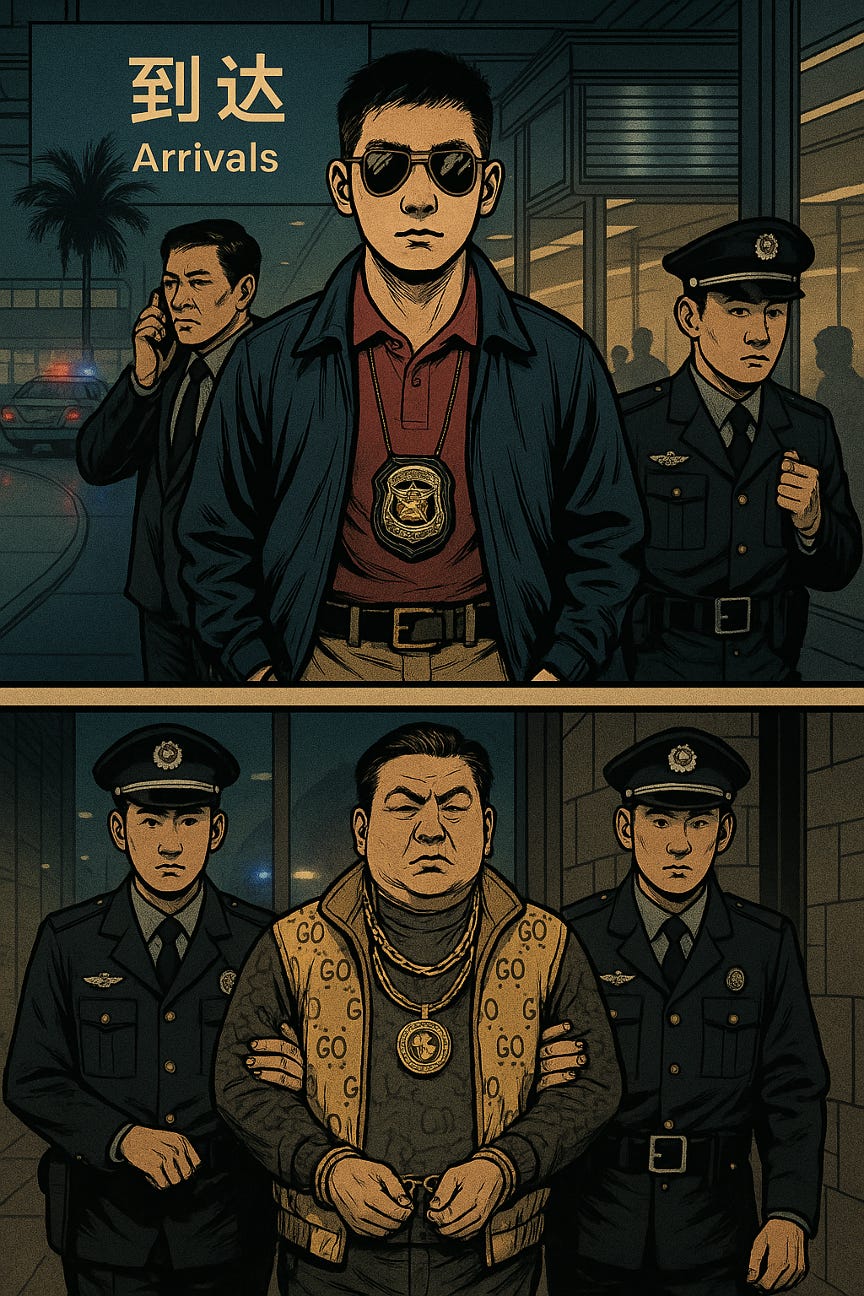

Personal Note: After disembarking a flight from Sihanoukville, Cambodia to Xiamen, China, I witnessed dozens of my fellow passengers arrested in front of live news cameras at customs. Present were around a dozen uniformed officers—alongside one plainclothes agent wearing khakis, a golf shirt, windbreaker, sunglasses, and a badge hanging from his neck – think Horatio Caine from CSI Miami.

I didn’t stick around long, but I caught enough to recognize what was happening. As he cuffed a middle-aged man in a Gucci tracksuit dripping with heavy jewelry, the plainclothes officer mentioned “illegal gambling operations.” It was fast, public, and clearly orchestrated for the cameras. My friend and I were the only foreigners there – we exited quickly and tried to avoid rousing suspicions.

A ChatGPT rendering the scene at Xiamen Gaoqi International as I remember it.

Chinese casinos like this one are a common sight in Sihanoukville, Cambodia these days. An idyllic beach resort once visited by Jackie Kennedy and other global jetsetters, the town has since descended into a gritty playground for China’s criminal underworld. Image source

The Gray Zone Advantage – Influence Without Ownership

In this context, the “gray zone” refers to the space between peace and open conflict—where states pursue strategic objectives through unofficial, unattributable, or legally ambiguous means. China has proven adept at operating in this space in a number of ways, most prominently through its maritime militias – an unofficial naval force disguised as fishing vessels increasingly used to press China’s territorial claims in the South China Sea. China’s indirect engagement with transnational criminal networks is another form of gray zone tactic as these actors offer Beijing a toolkit for reshaping environments abroad —without the political costs of formal intervention. However, as we will see in the coming parts of this series, these tactics do not always work out in China’s best interest.

Criminal syndicates aligned with Chinese interests can quietly destabilize adversaries, erode governance, and undermine legal norms. Through illicit logistics routes, offshore gambling hubs, and informal banking networks, they create parallel corridors of capital and influence that operate beyond the reach of traditional regulatory regimes. These networks have become deeply embedded in weak and fragile states—from Cambodia to Mali—where enforcement is limited, corruption is entrenched, and the allure of Chinese money often overrides accountability. The result isn’t just corruption—it’s a quiet erosion of sovereignty in regions where enforcement is weak, capital flows are opaque, and China’s informal proxies move faster than state regulators can track.

But the reach of these ecosystems doesn’t stop there. In Western societies, these criminal groups intersect with real estate markets, underground financial systems, and diaspora-linked political influence efforts. From Vancouver’s “snow washing” phenomenon to United Front-linked surveillance in Sydney and Toronto, Chinese-aligned networks have quietly moved billions and shaped elite ecosystems—often under the radar of traditional law enforcement.

Across all settings, the strategic advantage is the same: plausible deniability. China benefits from the reach and flexibility of these actors—reaping access, leverage, and insulation—without incurring the costs of formal involvement. When scrutiny intensifies, officials can disavow any connection. But by then, the strategic value has often already been extracted: institutions have been strained, norms undermined, and influence embedded. The disorder serves a purpose—and attribution remains elusive by design.

Looking Ahead – Setting the Stage for Parts II & III

This first part provided an overview on how China quietly benefits from transnational criminal ecosystems—not by directly commanding them, but by tolerating and, at times, subtly enabling them. These networks blur the boundaries between profit and policy, crime and strategy. But the story doesn’t end with deniable influence.

Part II will examine how financial nodes like crypto brokers, shadow banking systems, and offshore economic enclaves have become vital components of China’s informal resilience architecture. In a future defined by economic decoupling and great-power conflict, these mechanisms may serve as critical lifelines—moving money, skirting enforcement, and keeping strategic initiatives afloat.

Part III will explore how these same networks entrench China’s presence across Southeast Asia and the broader Global South, empowering its geopolitical reach through informal supply chains, regulatory arbitrage, and captured digital infrastructure in preparation for an uncertain future.

To understand tomorrow’s strategic competition, we need to understand the infrastructure no one officially owns—but that many quietly rely on.

Enjoying this deep dive?

Part I of China’s Gray Zone Syndicates is free to read — but Parts II and III will be available exclusively to paid subscribers.

If you value original, high-impact research on illicit finance, geopolitics, war, energy, and more, consider supporting this work by becoming a founding or paid subscriber.

🔒 Unlock the full series — and future investigations — by subscribing now.

Case in Point: Scale and Pattern - In just the first half of 2024, Chinese authorities repatriated over 920 suspects from Cambodia tied to online fraud and illegal gambling. UNODC reports show that scam compounds across Southeast Asia now employ tens of thousands—often trafficking victims—linked to Chinese criminal syndicates. U.S. Treasury sanctions against Huione Pay and related actors underscore the scale: billions in illicit crypto flows tied to human trafficking, terrorist financing, and fraud.