Understanding China's Global Ambitions – Part 1: A Violent Thrust Into Modernity

China's increasingly prevalent role on the world stage is not easy to explain, which is why I am doing it over three parts. We're doing something a bit different here: I hope you enjoy.

Paid subscribers gain exclusive access to the audio version of this article. Check it out here!

For other parts of this series, please see:

Part 4 - Coming soon!

China is making more global headlines by the day. Whether it's grand international investment projects, controversial trade practices, or increased military posturing, China's role in the global system is increasingly prominent and often puzzling to observers.

We at Between the Lines have devoted past articles to China's often controversial role in the global system. People frequently ask me the reasons behind some of these events, and I, having studied Chinese history for much of my life and lived there for five years, struggle to give them brief answers. This series attempts to shed some light on what guides the Chinese system today by delving into the country's geography and social, military, and economic history.

In this first part of a four-part series, I will do my best to explain the circumstances that made China what it is and continue to guide its actions on the world stage. Parts two, three, and four - exclusively for paid subscribers - will explore how these factors continue to shape China's actions in the 21st century amid many new challenges. I cannot claim total ownership over all of the ideas presented here, as I have the works of many Chinese and Western scholars I've read over the years to thank. However, these ideas form the basis of my understanding of this subject matter, which I am happy to share with all of you.

In writing this, I hope to provide you with a better understanding of the Chinese system so that it may help you interpret ongoing and future events as they unfold. Enjoy.

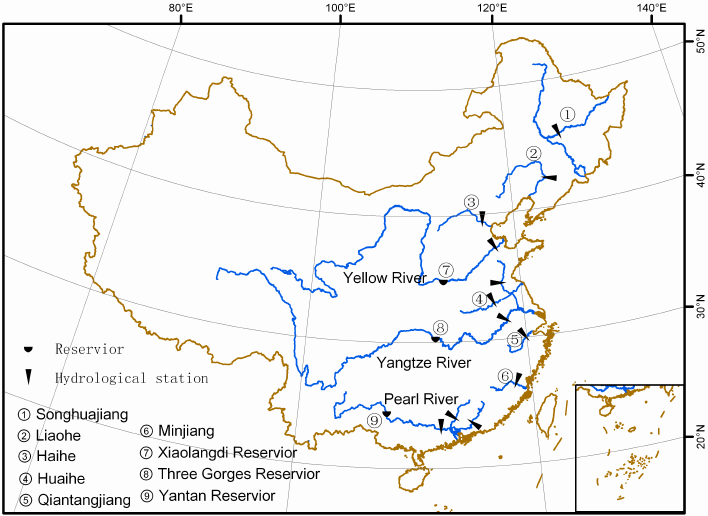

China’s major rivers all flow from the mountainous west to the east coast, providing most of the country’s freshwater resources. Image source

Geography shapes history

Chinese civilization originated on the plains along the Yellow River millennia ago. Estimates vary, but this occurred sometime in the past 4,000 – 6,000 years, making it one of, if not the, oldest civilizations on earth. The Yellow River is often described as 'China's sorrow' due to its frequent shifting along the silty plains that give it its eponymous yellowish hue, causing devastating flooding that continues to this day. Because the soil of this region is among the world's richest farmland, the people living in the area developed advanced means to cope with these catastrophic floods, including highly organized societies and advanced engineering. Various dynastic kingdoms sprung up here until 221 BCE when the region united under the reign of Qin Shi Huang, China's first emperor and founder of the Qin Dynasty, the reported origin of the word China.