The Islamic State's Growing Threat to the West

The Islamic State and its IS-K affiliate increasingly target Western countries. Given their track record, these threats should be taken very seriously.

The FBI alerted Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) about suspected IS operatives in the United States. Image source

On June 11, US authorities arrested eight suspected members of Islamic State-Khorasan (IS-K) in Los Angeles, New York, and Philadelphia. The suspects, all Tajik nationals, entered the US through the southern border. Although authorities do not claim these arrests were in connection to an active plot, they come as part of a larger wave of arrests and detentions of IS-K and other Islamic State operatives in Western countries in recent months. In the past two months alone, authorities have arrested suspected IS operatives in Italy, Spain, Georgia, and Germany, where one suspect attempted to infiltrate the ongoing UEFA European Football championship. Other foiled plots include one targeting the Summer Olympics in Paris, France, one targeting the Swedish parliament, and others in Idaho, US, and Dusseldorf, Germany.

Terrorist threat levels in the West have not been this high since 2016–2017, during the height of IS transnational operations. This latest threat surge, likely the product of factors such as the war in Gaza and IS-K’s ever-growing international focus, could have grave consequences for the West. With security agencies relatively unprepared for this deluge of IS operations, it is perhaps only a matter of time before there is a deadly attack on Western soil.

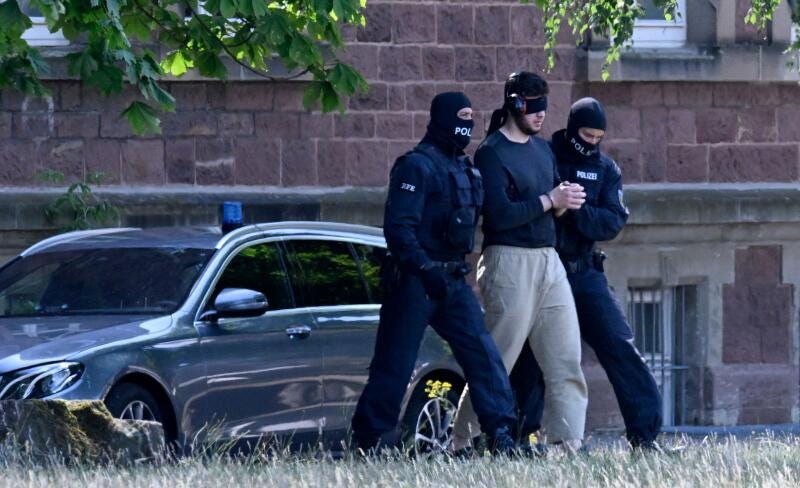

Police in Belgium, Germany, and the Netherlands arrested nine suspected members of an IS-K cell in a joint operation last summer. Image source

IS-K at the forefront of threats to the West

IS-K, also called ISKP, is at the forefront of its parent organization’s international operations. This position became especially apparent at the beginning of this year after the group conducted mass-casualty attacks in Kerman, Iran, and Moscow, Russia. The affiliate, which was previously entirely focused on establishing a caliphate in the Afghanistan-Pakistan region, began looking outward in 2020. That year, German police foiled a plot by a Tajik IS-K cell to attack US and NATO military bases in Germany.

IS-K has a complex strategic vision internationally. On one level, it remains intent on increasing its presence in South and Central Asia, as evidenced by advances in propaganda tailored to local audiences, such as the 2022 release of its Pashto language magazine, ‘Khurasan Ghag.’ Likewise, in 2022, IS-K expanded the production and dissemination of propaganda focused on Central Asian audiences as part of a broader push to reorganize its media apparatus that started in 2021. These audiences, especially Tajik nationals, are pivotal to IS-K’s external operations, which we have covered in previous editions of Between the Lines. On another level, IS-K seeks to expand its operations in the West, and the group’s propaganda offers insights into its goal.

Aside from recent calls to attack the Paris Olympics, IS-K has commanded its operatives to target the ongoing ICC Men’s T20 Cricket World Cup in the US. The affiliate has an extensive record of threats against Western countries, which it often labels as “crusaders” and “Zionists.” For example, in March alone, the IS-K’s Al-Azaim Media Foundation threatened France, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom. The IS-K also ran an article series against Western countries and their activities in its English-language Voice of Khurasan magazine and regularly incites supporters in Europe and the US to wage jihad at home.

IS-K maintains a track record of following through on its threats. For example, the Moscow attack did not occur in a vacuum. The IS has listed Russia as an enemy since its 2014 founding, citing a list of grievances, including the alleged persecution of Muslims in Russia and the country’s previous military involvement in Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Syria. IS-K has specifically also released a steady stream of materials against Russia over the years, such as articles and pamphlets criticizing its relations with the Taliban in Afghanistan, the IS-K’s most significant enemy. In addition to the Moscow attack this year, the IS-K has also targeted Russian assets abroad, including the 2022 bombing of the Russian embassy in Kabul, Afghanistan.

Similarly, IS-K has conducted several notable attacks in Iran prior to the 2024 bombings in Kerman. The affiliate claimed responsibility for shootings at a shrine in the southwestern city of Shiraz in October 2022 and an attack on a military parade in Ahvaz in September 2018. These incidents followed frequent propaganda releases against Iran that criticized it for being a Shia regime (and therefore a country of “murtad” or non-believers”), its assistance to the Assad regime to fight the IS in Syria, its relations with the Taliban government in Afghanistan, and its role in the Hamas attack on Israel, which it claimed was an anti-Sunni plot. Direct links also exist between IS-K’s propaganda and an uptick in plots or attacks in other places, such as Pakistan and Turkey.

The IS-K’s brutal attack on Moscow’s Crocus City Hall demonstrates the group’s growing ability to strike targets beyond its traditional region of operations. Image source

Threat perception in the West

Western security agencies are increasingly warning of the threat posed by the IS and its affiliates. On June 11, the head of Germany’s domestic intelligence agency warned that “the risk of jihadist attacks is higher than it has been for a long time.” In the Netherlands, authorities have raised the terror threat level to 4, signaling the realistic likelihood of an attack. Authorities in the US have forwarded a similar assessment, with Attorney General Merrick Garland saying that the “threat level has gone up enormously.” Many of these assessments have explicitly referenced IS-K or reiterated earlier statements by US military commanders such as Mark Kurilla, who in March 2023 warned of the group’s “operation against US or Western interests abroad in under six months with little to no warning.”

Considering these assessments, an attack on US or European soil is very likely in the coming months, especially amid the growing frequency of plots and arrests and IS-K’s record of following through on its threats. The group has been able to mobilize small teams of operatives to conduct attacks, including newly radicalized members, especially in Western Europe, where there are large Central Asian diaspora communities. These operatives are believed to be guided by an inner layer of around 80 foreigners who plot attacks while remaining under the radar. In recent years, there have been dozens of examples of IS operatives, including IS-K members, relying on virtual guidance from planners located elsewhere to select targets and arrange logistics.

Security agencies in Western countries appear to be overwhelmed, allowing IS-K cells and lone sympathizers inspired by the affiliate to exploit gaps as they arise. The burdening of security capabilities is primarily due to the general rise in jihadist propaganda, including by groups such as al-Qaeda, as well as associated online disinformation amid the war in Gaza. This information overload is compounded by an exponential increase in online activity related to the conflict, making it difficult to separate real threats from false alarms. In the US, the counterterrorism gaps are also a product of declining interest in combatting jihadism, with other strategic choices, such as great power rivalry, taking precedence.

The threat from IS in America has traditionally been homegrown, with a disproportionate number of plots or attacks inspired by the group rather than those directed by it. The IS believed that, during its jihadist wave between 2014–2019, it was easier to inspire sympathizers to commit attacks in their home countries than to send operatives abroad. Now, it appears that IS is exploiting the migrant crisis by embedding its operatives into cross-border flows, going against the historical data that shows a low incidence of terrorist activity from illegal migrants.

Aside from recent arrests in the US, authorities have identified smuggling rings that have helped bring IS members into the country. Authorities have also found some IS members living in the US for years, virtually undetected. While it is unclear to which branch these operatives are affiliated, the fact that most are of Central Asian descent likely points to IS-K involvement. Still, there is no geographical pattern to IS-K arrests in the US. Traditionally, it has been challenging to analyze patterns in the arrest of local IS sympathizers, who generally come from diverse age brackets, family backgrounds, and belief systems.

IS-K maintains a powerful presence in South and Central Asia, where it recruits many individuals into its growing ranks. Image source

Conclusion

The IS, led by its ambitious South/Central Asia-based affiliate IS-K, is inching closer to launching a successful attack in the West while vexing authorities there. The IS-K has repeatedly proved to be agile in the face of counterterrorism pressure and can act on its threats. It possesses many tools, ranging from networks across Europe and the US to a large audience of sympathizers and sophisticated messaging. The group poses an urgent and extreme threat in the West, where security agencies may be overwhelmed by an alarming spike in threat activity and possible diffusion of their focus amid rising great power competition.