The Geopolitics of Natural Gas: How America Gained Primacy over Russia in the European Gas Market

America's massive role in the global natural gas market may have changed practically overnight, but it was the culmination of decades of developments elsewhere.

An LNG carrier, part of as series of developments that have changed both global gas markets and geopolitics as a whole. Image source

For Part 2, click here

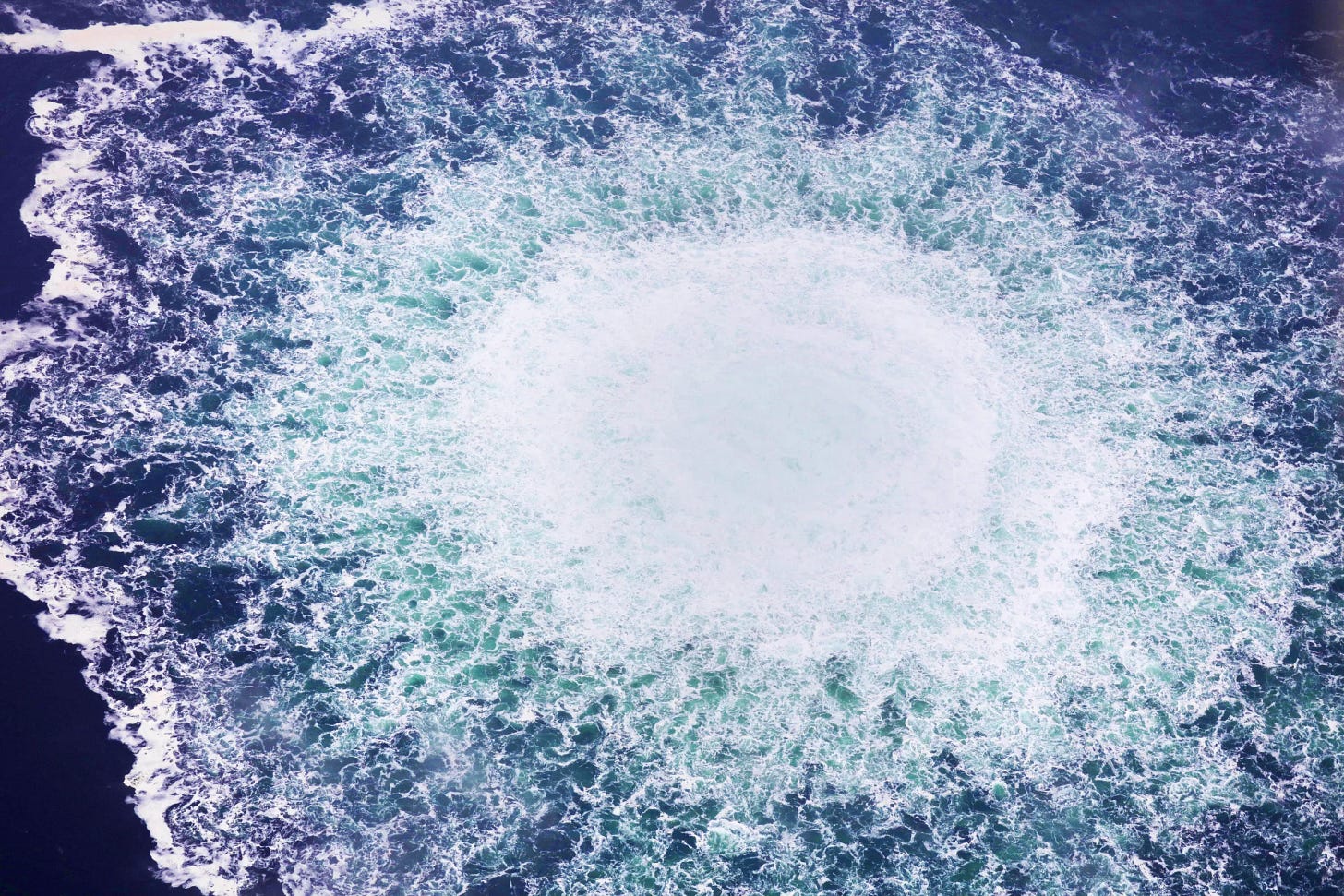

On September 26, 2022, a series of four explosions on the Baltic Sea floor sent shockwaves across Europe and around the world. Saboteurs had set these explosive charges along the Nord Stream 1 and 2 gas pipelines that connect German and broader European markets to vast natural gas fields in northern Russia. According to the United Nations, the explosions caused what may be the greatest gas leak in history, releasing some 478,000 tonnes of methane into the atmosphere – the annual emissions equivalent to 1.3 million cars or a third of Denmark's national total.

This event marked a significant turning point in the global gas markets. It was not just a series of explosions, but a profound shift that was the culmination of decades of developments, which we explore in this article.

Gas bubbling up from the exploded Nord Stream pipelines. Image source

Natural gas and the emergence of pipeline politics in Europe

Humans have known of and used natural gas for millennia, and it became widely commercialized during the Industrial Revolution when Great Britain used it to fuel lighthouses and streetlights starting in 1785. In 1821, the city of Fredonia, New York, constructed the world's first gas pipeline to light homes in the area. By the first half of the 20th century, American industry constructed gas pipelines across much of the continental United States as the substance became increasingly used in heavy industry, power generation, home heating, fertilizer production, and other applications. Other large landmass countries, such as Canada and the Soviet Union, followed suit, constructing increasingly long and complex pipeline systems to fuel their burgeoning industrial economies.

Natural gas became a significant factor in geopolitics in 1968 when the Soviet Union made its first gas exports to Europe via the Brotherhood pipeline to Austria. Over the next few years, other Western countries such as West Germany, Italy, and France followed suit, increasing economic interdependence on either side of the Iron Curtain amid a thaw in the Cold War. It was a perfect partnership from an economic perspective. The Soviet Union had abundant cheap gas after extensively developing the country's vast fields starting in the Second World War. Western Europe's demand for energy skyrocketed due to heavy post-war investment in its export-driven industrial economy. By the 1980s, the Yamal gas pipeline exported an ever-growing supply of Soviet natural gas to Europe, despite protests from Washington over the Soviet War in Afghanistan and concerns over Europe's growing dependence, which the CIA assessed could impact European foreign policy to favor Soviet interests.

Soviet gas sales to Europe were highly lucrative and helped fund the country's increased military spending during the Brezhnev era and beyond. However, this spending, coupled with a collapse in oil prices and a costly war in Afghanistan, contributed significantly to the Soviet Union's collapse in 1991. Although the former Soviet economy had also collapsed, Russian gas sales to Europe exceeded 100 billion cubic meters (bcm) for each year of the tumultuous 1990s and expanded to over 160 bcm in the 2000s. Although Russia privatized much of its oil industry in the 1990s, gas exports remained primarily under the state-controlled Gazprom. During his first year in office, Vladimir Putin used state funds generated by Gazprom to return the company to majority state ownership. He later used the firm to acquire the assets of his defeated political foes. Thus, for over five decades, Soviet and later Russian gas sales to Europe provided a stable and lucrative revenue source for the state, helping fund projects that were core to its interests.

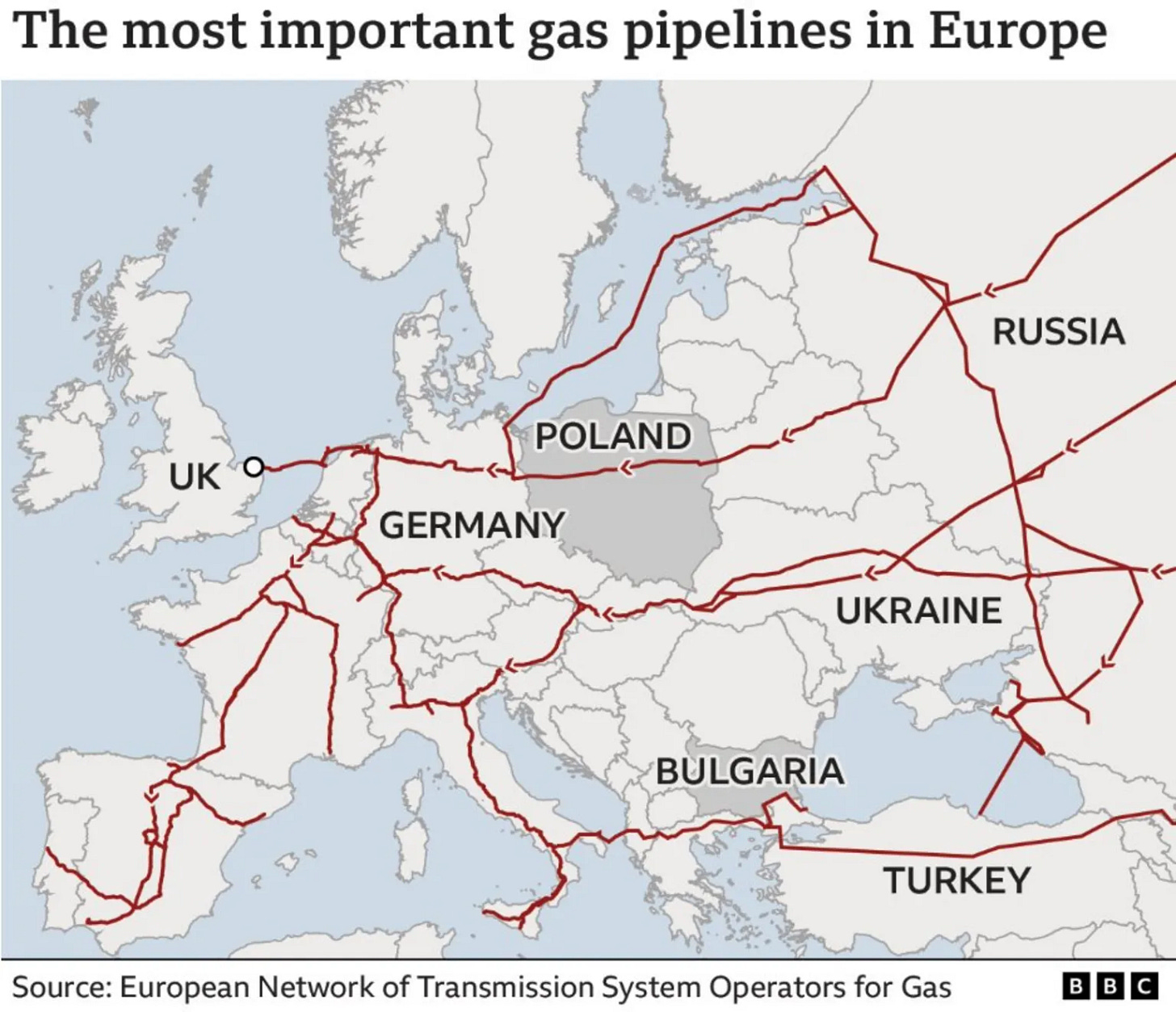

Europe remained highly dependent on Russian energy, and relations between Russia and the EU remained relatively cordial despite rising tensions on the world stage. However, by the late 2000s, European policymakers expressed growing concerns about their dependence on Russian gas, particularly after Moscow's August 2008 invasion of Georgia. That year, policymakers planned the Southern Gas Corridor pipeline that bypassed Russian pipeline systems to bring gas from the Caspian Sea to the European market through Türkiye. With the project's final leg completed in 2020, the pipeline can deliver 10bcm of non-Russian gas to the European market. Although Europe increasingly relied on other pipeline exporters such as Norway and Algeria, Russia remained the most significant supplier, with more 150bcm delivered via its pipelines in 2021.

By the 2020s, Russian pipelines remained Europe's top gas supplier. Although Washington regularly protested Russia's Nord Stream 2 pipeline expansion – which would have delivered an additional 55bcm to the European market upon completion – US Secretary of State Antony Blinken admitted that sanctions stemming from Russia's 2014 annexation of Crimea would not block its completion in a June 2021 speech. However, Russia faced growing competition from abroad, with imported liquified natural gas (LNG) gaining a growing foothold in the market. Then came 2022, which saw the most profound change in global energy markets in a century; one that will affect the global market for decades to come. None of this change would have been possible without the technological and economic means to transport gas by sea in a liquified form; a means that increasingly serviced markets on the other side of the world.

A BBC Map highlighting Europe’s gas pipeline infrastructure. Image source

The rise of LNG in Asia and the Shale Revolution

Although pipelines remained the most significant and economical means of transporting gas internationally until the 2020s, LNG shipments had grown in prominence, largely due to the influence of the US. By 2020, just 53% of global gas exports were sent via pipelines, and the US, Australia, Qatar, and other LNG exporters had made inroads into the European market, supplying 22 bcm there in 2021.

Although the world's first international LNG shipment departed the Louisiana Gulf Coast for the UK in 1959, the Asian markets popularized the technology, starting with Japan's first arrival in 1969. By the 1970s, South Korea and Taiwan began importing LNG to feed their rapidly expanding industrial demand. Brunei and Malaysia emerged as major regional suppliers with the help of US and Japanese investment in the 1980s. This popularization of LNG technology, combined with a dramatic increase in supply, made non-pipeline exporters important players in the global gas market and geopolitics as a whole. Global sellers and buyers invested billions of dollars in gas liquefaction plants, port infrastructure, regasification plants, and local pipelines to facilitate the burgeoning LNG trade over the succeeding decades.

Japan and the Asian Tigers' (Singapore, Hong Kong, South Korea, and Taiwan) rapid industrialization in the 1970s and 1980s required a massive influx of energy to the region as none of these places have significant natural resources at their disposal. Moreover, each is an island-based territory, either by geography or political circumstance, making transnational gas pipelines impossible. For these reasons, Japan and the Asian Tigers were willing to pay a premium to import natural gas by ship and invest billions in the necessary infrastructure to do so.

China's rapid industrialization in the 1990s and 2000s accelerated this trend. Unlike most of its neighbors, China has relatively abundant natural gas supplies derived from its extensive coal reserves and limited domestic oil fields. However, despite these resources and ongoing attempts to increase domestic production, China still imports 42% of its natural gas supply and is now the world's largest gas importer. Due to its large landmass and many borders, China has been able to import much of its gas needs via pipelines linking it to Central Asia, Russia, and Myanmar. However, these pipelines still fall short of China's gas import needs. Although Russia claims it will expand its Power of Siberia pipeline system to China, the two countries cannot agree on funding, leaving it in an effective deadlock. For this reason, China has also emerged as the world's largest LNG importer, with seaborne LNG accounting for some 60% of its imported gas at present. India and Southeast Asia have also emerged as significant LNG importers as - like the Asian tigers – most of these countries are islands either practically by geopolitical circumstance, at least when it comes to natural gas. These massive Asian markets continue to normalize and inspire innovation in the global LNG trade.

By the 2000s, Asia's rapid rise in demand for LNG coincided with a dramatic increase in supply. Major LNG exporters such as the United States, Australia, Qatar, and regional players such as Brunei, Indonesia, and Malaysia had steadily increased their output to meet Asia's rising demand. Russia also satiated some of Asia's LNG demand through its Sakhalin II LNG terminal, the product of joint Western and Japanese investment. Moreover, by the 2010s, shale oil and gas – which extracts previously unattainable 'tight' supplies using hydraulic fracking technology – significantly increased natural gas supplies in the United States and elsewhere, flooding the global LNG market.

After substantial infrastructure investment along the eastern and Gulf coasts, the US began exporting LNG from the lower 48 states for the first time in 2016, immediately becoming a top global supplier. Shale technology also allowed Australia to dramatically increase its LNG exports, and it supplied around 53% of China's market in 2019, up from 40% just three years prior. Although the US has become one of the world's largest natural gas producers and an important player in Asian LNG markets, most of its LNG export infrastructure lies on its Atlantic and Gulf coasts, far from the Pacific markets. Moreover, Europe's dependence on cheaper Russian pipeline gas hindered America's LNG export prospects, although American producers had made significant inroads into the European market by the late 2010s. Then came 2022, when Russia's invasion of Ukraine made Europe's gas markets more internationally competitive than ever before.

A planned LNG import terminal in China’s Shandong province. Image source

America’s LNG liquefaction plants. Image source

Continue to Part 2…