Supply Shortages: How Ukraine and Russia Address this Key Strategic Challenge

Both Russia and Ukraine are struggling with supply shortages following two years of heavy fighting. Moscow appears to have the upper hand.

Ukrainian soldiers are increasingly forced to ration their munitions and rely on outdated equipment due to an ongoing shortage of supplies. Source

On February 19, Russian troops broke through defence lines in Avdiivka, taking the city. Footage showed Ukrainian soldiers escaping through a small corridor – some of them on foot – amid the crack of gunshots and billowing smoke from freshly exploded artillery. The city that once boasted a population of around 30,000 was reduced to columns of debris and heavily damaged buildings. The recapture of Avdiivka came as Russian forces capitalized on their superior numbers and supplies over those of their Ukrainian counterparts.

Although Moscow still suffers from shortages, its ability to harness its vast industrial base to produce weapons and its relationships with international partners to source them have given it a strategic advantage over Kyiv, which grows increasingly desperate. With shipments of long-promised U.S. and E.U. aid currently held up, the situation for Ukraine grows more dire by the day.

Moscow jumpstarts its arms industry, relies on foreign partners

Although Moscow suffered many military setbacks early in the war, it continues to make strides toward addressing the principal challenge of supply problems. Much of this is done on the home front as the country maintains a clear material advantage over its opponent regarding industrial capability.

Although Russia successfully increased its domestic weapons output over the past several months, it continues to deal with shortages. During an interview with RBC-Ukraine, Major General Vadym Skibitsky of Ukrainian military intelligence claimed that Russia’s rising weapons output is relatively insignificant and that everything it produces, it sends to the front lines. He also claimed that much of its stockpiled weapons are out of date. Despite this, General Skibitsky noted that Russia’s enactment of legal changes allows its defence sector to increase output over time, with factories now working more days per week to produce weapons – primarily artillery systems and armoured vehicles.

Artillery shell production is vital to the Kremlin’s war effort as these inflict 80–90 percent of casualties against Ukrainian forces. Artillery batteries used to beat back advancing soldiers and devastate existing lines are essential to the Russian war effort. Moreover, Russian innovation in advanced targeting techniques allows its batteries to vastly outperform those of other countries, bringing effective fire within three to five minutes compared to a standard 20 to 30 minutes. During the first year of the war, Russia launched an estimated 10–11 million artillery rounds – much of its estimated prewar stockpile. Shell production was estimated to be around one million new rounds annually in 2022, reaching an estimated 3.5 million units last year and predicted to reach 4.5 million units in 2024. Although these gains are substantial, domestic shell production remains insufficient to keep pace with the demands of the front.

Missile production is a similar story. In February 2023, Russia reportedly produced less than 50 missiles per month. Production has since risen to an estimated 115–130 short-range missiles per month due to efforts to resume production at long-dormant factories and the likely sourcing of components from consumer electronics imported from China. Although Russia is unlikely to run out of missiles, it seeks creative means to fill this production gap. Domestically produced loitering munitions (exploding drones) – made from modified consumer racing drones – have been used to offset shortfalls but remain unable to fully compensate for the deficit.

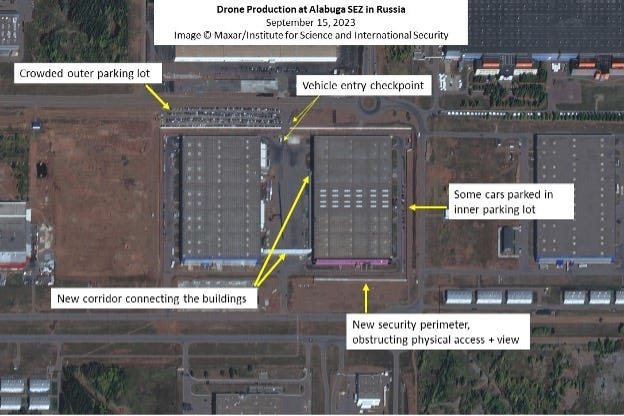

Russia’s imported Iranian Shahed kamikaze drones are more effective on the battlefield than its modified commercial drones. Russia has deployed nearly 4,000 Shahed-131 and 136 drones since 2022 and plans to manufacture its own. Renamed the Geran-1 and Geran-2, respectively, these Russian versions of the Iranian models are manufactured at a Tatarstan-based facility that intends to produce 6,000 units annually by 2025, according to leaked documents. These documents also show that although the factory was behind schedule in late 2023, it could now exceed its initial targets. The factory reportedly produced some 1,100 units to date, improving on the initial design of these by using superior engines and stabilizers.

Iran also provides Russia with a large number of surface-to-air and ballistic missiles, including around 400 Fateh-110 road-mobile missiles, which arrived in January. These also help bolster Russia’s supplies, reducing the chances of battlefield shortages.

Russia also works extensively with international partners—with whom it has longstanding arms provision arrangements dating back decades—to source weapons and munitions compatible with its Soviet-era equipment. According to South Korean intelligence, North Korea reportedly sent over 6,700 shipping containers loaded with millions of rounds of munitions in exchange for food between September and February. Reports indicate that Pyongyang possesses vast stocks of Soviet-era munitions compatible with Russia’s current delivery systems. Last October, photos emerged of Russian soldiers using North Korean projectiles on the Ukrainian battlefield.

According to the Wall Street Journal, a Russian delegation approached the Egyptian government in April 2022 and successfully purchased over 100 Soviet-era helicopter engines. Russian delegations also reportedly came to the governments of Belarus, Brazil, and Pakistan in attempts to replenish their supply of transport helicopters. Similarly, Nikkei Asia found evidence last June that Russia was repurchasing tank parts and missiles previously provided to India and Myanmar.

Moscow also uses its superior economic power to deny Ukraine access to Soviet-era munitions stockpiles needed to further its war effort. In one example, Ecuador was forced to back out of an arrangement brokered by the U.S. for it to supply Ukraine with outdated Soviet weapons in exchange for a $200 million weapons deal. This was primarily due to Moscow’s temporary ban on Ecuadorian bananas and flowers that forced Quito to capitulate.

An image from Russia’s drone production facility in Tatarstan. Source

North Korean artillery shells found in Ukraine. Source

Ukraine faces severe shortages amid delayed international aid

Although Russia faces challenges, Ukraine’s struggle to replenish its stocks of ammunition and artillery shells to more advanced systems such as drones and air defence missiles is much more severe. Moreover, this struggle is a very public one, as senior Ukrainian soldiers, officials, and President Volodymyr Zelenskyy appeal to allies around the world for aid.

Although Kyiv attempts to reduce its reliance on Western weapons and increase its domestic production, its current stocks are marred by old equipment, forcing the country to carefully manage its use of Western weapons systems and find other ways to fight as cheaply as possible. Domestic production is a significant challenge for Ukraine as restarting its domestic arms industry requires licenses to produce modern weapons and millions of dollars of investments. This challenge is further exacerbated by the damage to its manufacturing infrastructure throughout the war. Although Ukraine’s drone production program is highly successful – the country reportedly produces 90 percent of its drones domestically – the ground war desperately requires more bullets and artillery shells, and soon.

With a limited domestic production capacity, Ukraine’s war effort remains highly dependent on foreign aid. In Washington, Congress is currently holding up more than $60 billion in assistance from the U.S. – by far Ukraine’s largest backer to date. Meanwhile, in Brussels, the European Union’s promise to contribute €50 billion to Ukraine will not be delivered in full until 2027 despite Kyiv’s current $40 billion budgetary shortfall.

Accusations of corruption continue to dog Ukraine’s war effort, including allegations that corrupt officials stole $40 million in funds intended for essential artillery shells this January. This latest plot reportedly included officials from the Ministry of Defence and defence contractor employees at Lviv Arsenal.

Ukrainian artillery shells captured by Russian forces in Avdiivka. Source

Recent changes around the two main buildings where Shahed-136 production is taking place in Russia. Building 8.2 (left) and 8.1 (right). Source

Conclusion

Russia’s nearly half a million better-equipped troops mobilized against Ukraine present a dire situation for Kyiv. Given their country’s funding shortfalls and lack of domestic capacity, Ukrainian soldiers face an increasingly difficult situation on the frontline as a result. Meanwhile, although Russia continues to effectively address its shortages, the vast quantity of weapons and munitions it used to batter Ukraine in its initial war effort has proven unsustainable. In this way, although Moscow apparently has the upper hand, this war could prove protracted and costly for both sides moving forward.