Organized Crime: Another Arm of China’s Gray Zone Tactics

A recent rise in global crime shines the light on China as a major state sponsor of illicit activity

China plays a vital role in the ongoing rise in global criminal activity and poses a serious threat in several countries. Known and alleged activity linked to China includes the trafficking of humans, narcotics, natural resources, and wildlife, cybercrime, money laundering, and various other illicit activities. Chinese criminal syndicates carry out these activities with the tacit support of the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which uses these non-state actors to further its geopolitical agenda as a grey zone tactic. This state-sponsored illicit activity not only fuels the ongoing spike in global crime, but also exacerbates ongoing conflicts.

CCP Links to Organized Crime

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has long been accused of maintaining mutually beneficial links with Chinese organized crime syndicates operating in foreign countries. The CCP allegedly uses these connections to extend its influence and protect its interests while exerting control over Chinese diaspora communities abroad. The links between the CCP and criminal groups are evident in many cases. For example, Wan “Broken Tooth” Kuok-Koi, the notorious leader of the Hong Kong-based 14K Triad, is also a member of the CCP and sits on the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, a high-level advisory body to the ruling party.

Over the past decade, China’s massive international investment under its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has spurred a pattern of organized criminal activity, particularly in major infrastructure hubs and special economic zones in Southeast Asia and Africa. Wan and his 14K triads attempted to legitimize their organization by linking their operations to BRI projects before US authorities imposed sanctions on Wan in 2020. Beijing has vowed to crack down on corruption related to BRI projects, with President Xi calling for a ‘clean BRI’ in 2017 and dramatically increasing the number of investigations against alleged cases of corruption in 2021, particularly those relating to embezzlement. Indeed, the party has pushed its elites to shed their overseas assets, reportedly in response to Western sanctions against Russian overseas assets. However, China’s recent BRI investigations primarily target embezzlement and assets rather than bribery, ties to known criminals, and other forms of corruption. Moreover, as with domestic corruption cases, Xi Jinping loyalists are likely immune to ongoing BRI anti-corruption probes.

The CCP relies on criminal groups to serve many functions abroad. In several cases, criminal groups have targeted regime critics and dissidents in Chinese diaspora communities, policing and silencing these individuals amid growing concerns at home. During Hong Kong’s large-scale protests in 2019, suspected triad members assaulted pro-democracy protesters on multiple occasions, often with alleged police impunity. These criminal groups often supplement the activities of China’s secret police, who are deployed globally for different functions, including tracking dissidents; China has reportedly opened over 100 police stations globally since 2016.

Criminal triad groups maintain substantial connections to legitimate businesses in China and overseas, using these businesses as fronts for illicit activities and money laundering. These groups take advantage of global transport systems to supply precursor chemicals for synthetic opioids such as fentanyl. Through these ties, Chinese criminal networks also provide services to other legitimate companies, fostering connections with international business and political elites while gathering information for the CCP.

In Palau, a small archipelago in the Pacific, high-profile Chinese criminals, including Wan “Broken Tooth,” have built connections with the country’s political elite – including two former presidents – reportedly at the behest of the CCP. Here, Chinese criminal groups operate illegal online gambling sites and sex trafficking rings while reportedly trying to sway elites in the strategically important Pacific island nation of just 18,000 people to end their country’s diplomatic recognition of Taiwan. In the Philippines, controversy erupted last month when authorities discovered that a local mayor was a Chinese citizen pretending to be Filipino. The mayor, Alice Leal Guo, had reportedly facilitated operations at a scam center operated by a Chinese criminal group in her jurisdiction, prompting growing concerns over the scale of Chinese influence in the country.

Alleged China-backed criminals attack pro-democracy protesters in Hong Kong in 2019. Image Source

Allegedly smuggled rosewood logs at a port in Shanghai, China. The high demand for these logs in China is funding an insurgency in Mozambique. Image Source

When Crime Fuels Conflict

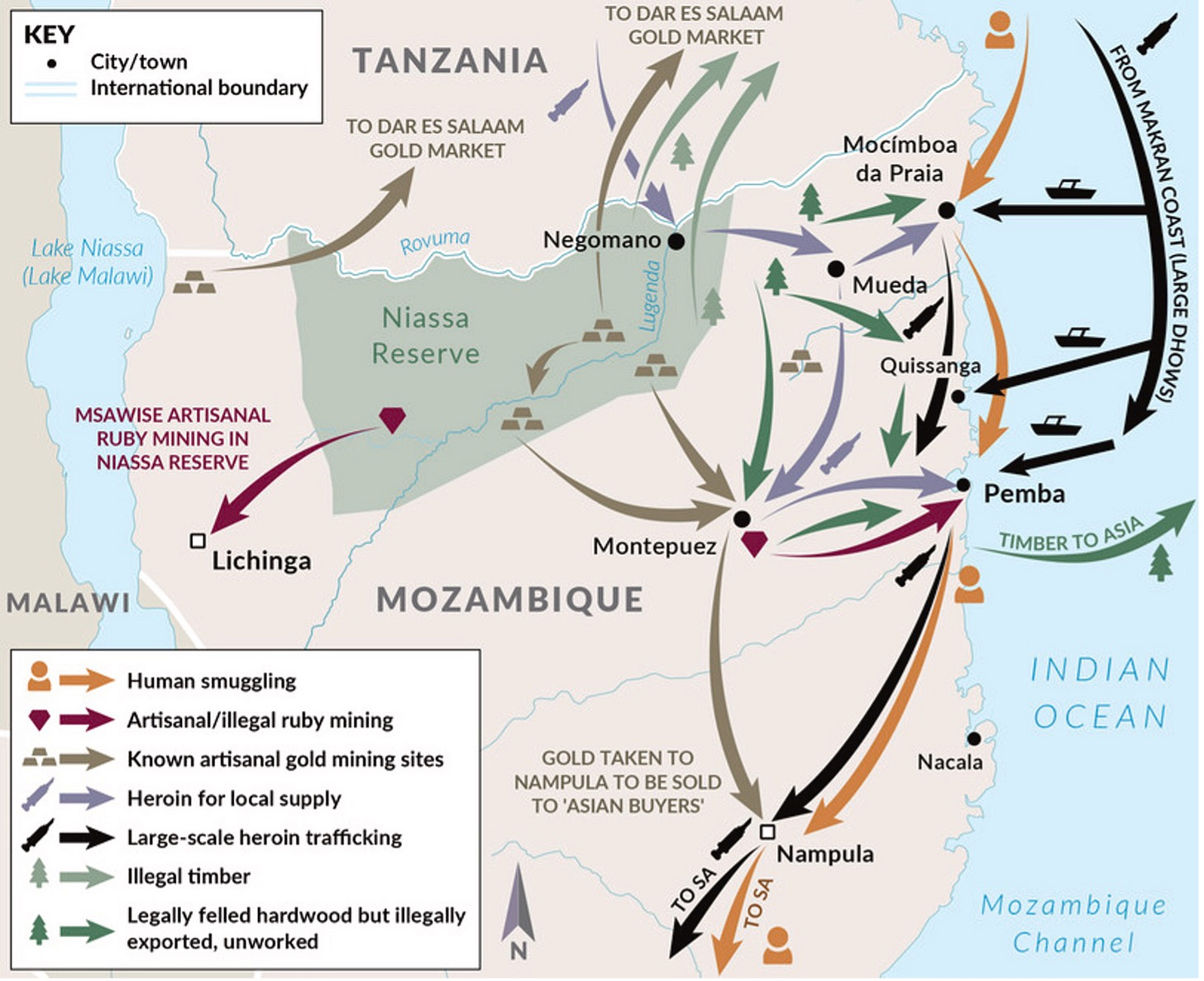

China’s criminal networks frequently exacerbate or fuel conflict around the world, particularly in Africa, where its economic, security, and criminal presence has dramatically expanded over the past decade. In northern Mozambique, where Islamic State insurgents have staged attacks since 2017 thanks in part to funds derived from illicit smuggling, Chinese criminals operate largely with impunity. According to an undercover probe by the Environmental Investigation Agency earlier this year, Chinese criminal groups have smuggled millions of metric tonnes of rosewood worth hundreds of millions of dollars out of the country and into China despite an export ban. The agency reports that this illegal trade provides nearly $2 million per month to the Islamic State-Mozambique.

Rosewood logs, likely illegally smuggled, at a port in Shanghai, China. The high demand for these logs in China is funding an insurgency in Mozambique. Image Source

Chinese criminal networks play an essential role as the money launderers of choice for Mexico’s hyper-militarized drug cartels, offering ‘clean cash’ more quickly and at cheaper rates than traditional methods. By offering high-quality money laundering services and providing precursor chemicals for synthetic opioids, Chinese criminals are fueling conflict and crisis on both sides of the US–Mexican border. Chinese criminals operate a vast underground banking system that allows cartel members to exchange vast sums of dollars for pesos using recruited Chinese couriers and legitimate businesses. In one case, members of the Sinaloa cartel in Los Angeles, US, laundered over $50 million through one of these schemes before they were apprehended by the US Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA).

Although China frequently uses criminal groups to further its interests, there are also many cases where these groups’ activities have negatively impacted China and its interests. Along China’s border with Myanmar and across the greater Golden Triangle region, Chinese criminal groups engage in many forms of illicit activity, including human, weapons, and narcotics trafficking, as well as cybercrime. Although the CCP and Myanmar’s junta regime have facilitated and benefited from these activities, the surge in cyber crime emanating from scam centers in the region has resulted in a public backlash in China. This backlash comes amid reports of the luring and abduction of Chinese nationals forced to work in these centers, as well as billions of dollars scammed from the Chinese public each year. Beijing’s subsequent cross-border crackdown exacerbated Myanmar’s escalating civil war and drove the scam operations south toward Thailand. Meanwhile, Chinese criminal networks continue to operate in Myanmar with the understanding that if they do not harm Chinese interests, they can operate without interference.

“The issue for Beijing [in Myanmar] is not the illicit economy; it is illicit activity that targets Chinese nationals,” said Morgan Michaels, the International Institute for Strategic Studies.

Conclusion

The growing influence of Chinese organized crime networks is a complex global security issue that requires coordinated efforts from law enforcement agencies, governments, and international organizations. Economic opportunities, diaspora communities, and the global reach of Chinese businesses fuel the growth of these networks. These criminal actors flourish in areas of weak governance, where they often become significant players in local economies and co-opt local elites. The CCP’s backing of these actors makes tackling the threats from this nexus even more challenging, as it aids Beijing in pushing agendas or securing interests. Chinese criminal networks will likely continue to pose a growing threat to many states, not only due to increased crime but also to Beijing’s use of them to push its geopolitical, economic, and security agendas.