New Caledonia Riots: Old Grievances hit the World Stage

Weeks of rioting in the French overseas territory of New Caledonia have brought longstanding issues there to global attention. With a negotiated settlement unlikely, further violence is a possibility.

A street blocked with debris from rioting in Nouméa. Image source

Over the past two weeks, members of New Caledonia’s indigenous Kanak community have been rioting across the French overseas territory located in the southwest Pacific Ocean. Thousands of rioters have looted shops and torched public infrastructure and cars in the capital, Nouméa, causing at least $1 billion in damages. Authorities have declared a state of emergency and are using armored vehicles to retake control of the highway linking the capital with its international airport. A countrywide overnight curfew is underway, and foreign governments have evacuated hundreds of citizens.

This violence comes in response to a controversial bill passed by the French parliament on May 14, allowing French residents who have lived in New Caledonia for at least ten years to vote in local elections. Ethnic Kanaks fear these changes, which have not yet passed into law, will dilute their vote in future elections, limiting their influence over local affairs. For over eight decades, Kanak groups and local French loyalists have engaged in heated debates over the territory’s independence, sometimes resulting in violence. With recent levels of violence not seen since the 1980s, New Caledonia may face a protracted conflict if Paris does not come to a political solution that is satisfactory to local indigenous groups.

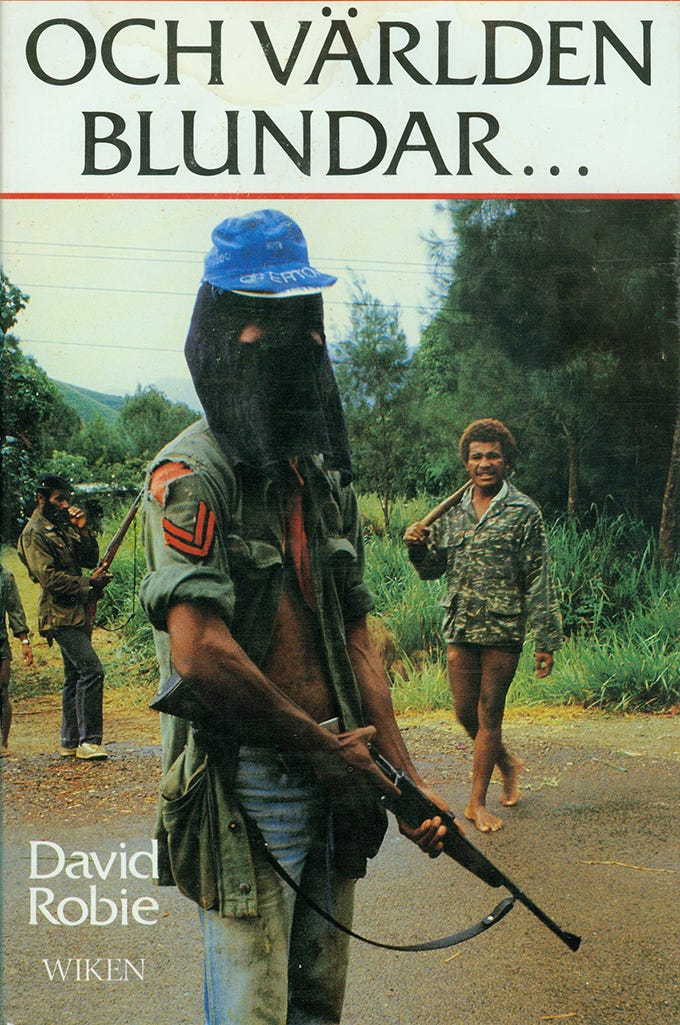

A masked insurgent on the cover of the Swedish book on the 1980s New Caledonia Insurgency titled ‘Blood on their Banner’. Image source

An economy in crisis

New Caledonia holds the fifth largest nickel reserves and is ranked third globally in mined nickel production, with the territory’s mining sector employing around 25% of residents. However, fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic and rising competition from Indonesia have caused prices to fall, threatening thousands of Kanak jobs. Local producers want to divest their holdings amid mounting losses and looming bankruptcies. One affected mine alone is responsible for six percent of New Caledonia’s GDP. Fears of a local industry collapse underscore much of the current violence.

Nickel is one of the world’s most strategically important assets because it is a critical ingredient in both stainless steel and electric batteries, which are essential to the ongoing energy transition. For years, France subsidized New Caledonia’s nickel industry to retain control of global nickel value chains. Global demand for nickel increased by 40% between 2017 and 2022, and policy documents issued by the US, Australian, and Chinese governments specifically list nickel as important to their strategic interests. In 2021, Tesla independently invested in New Caledonia’s Goro mine in a first-of-its-kind direct deal with a supplier in the Pacific.

The recent violence has sent shockwaves throughout the global market. The price of nickel on the London Metal Exchange has risen by 15% to $21,275 per metric tonne since May 8, despite abundant global supplies. These price gains are primarily due to New Caledonia’s outsized role in the global nickel supply chain. For example, the territory’s Doniambo and Koniambo nickel processing facilities account for close to a quarter of the global supply used to make ferronickel, a critical component in stainless steel production. With violence the worst it’s been in decades, France is now under pressure to deliver a political resolution to a problem rooted in nearly two centuries of historical divisions.

Recent riots reportedly caused up to $30 million in damage to Brazilian mining conglomerate Vale’s nickel plant. Image source

Historical divisions

New Caledonia is a chain of islands about 900 miles east of Australia. Its capital, Nouméa, is located on the main island of Grand Terre. The indigenous Melanesian Kanak people comprise 41% of the territory’s population, while Europeans constitute 24%, and 35% are ‘others,’ mostly immigrants from nearby Pacific islands. The Lapita people – ancestors of the Kanaks – first settled the islands around 1500 BCE, and the first Europeans arrived in 1774 during the second voyage of English explorer Captain James Cook. European merchants increasingly visited the islands and, by the 1840s, began trading sandalwood extracted from there and taking thousands of locals to work as indentured laborers in plantations elsewhere.

France took possession of the islands in 1853 to further its military and commercial interests in the Pacific. It also established a penal colony there. In 1864, French geologists discovered massive nickel reserves on the banks of the Diahot River and in the rugged mountains of Grand Terre. France soon developed extensive mining operations on the island, dispossessing Kanaks of much of their land. In 1878, the native Kanaks launched their first major war against European settlers and their commercial interests.

In 1946, New Caledonia officially became a French overseas territory, giving its residents the right to French citizenship and making the French president their official head of state. Tensions between Kanaks and Europeans continued to simmer until the 1970s when Paris actively encouraged European migration to the territory. The reasons for this active encouragement were twofold: first, French miners needed laborers to expand production, and second, the influx of migrants established a “non-indigenous majority,” stifling calls for independence.

The influx of migrants caused tensions with the Kanak to simmer until 1984 when the pro-independence Kanak and Socialist National Liberation Front (FLNKS) party boycotted regional elections. FLNKS operatives vandalized town halls and set into motion a four-year quasi-civil war, known colloquially as “the events.” During this period, independence activists partook in incidents of armed violence, hostage-taking, and widespread rioting.

The 1998 Nouméa Accord set up a constitutional framework for New Caledonia in which France transferred all political powers to local leaders, aside from sovereign matters such as defense. Crucially, the accord also established means to hold up to three referendums to decide whether the territory should be completely independent. The first of these referendums was held in 2018, with 56.4% of voters choosing to remain with France. In the second referendum of 2020, this figure fell to 53.26% of votes.

The third referendum of December 2021 turned controversial when Kanak groups requested to delay voting due to the spread of COVID-19 among many members of their communities. France disregarded these calls, resulting in a voter turnout of just 44%, with just 3.5% voting in favor of independence. France’s conduct in the lead-up to the vote provoked further divisions with many Kanak groups in the territory.

New Caledonian politics are characterized by worsening divisions between French loyalists (left) and Karak nationalists (right). Image source

Socioeconomic factors

The ongoing violence is as much a product of deep-seated economic and social grievances as it is of the Kanak quest for independence. In 2011, a UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples noted:

“The Kanak people are experiencing poor levels of educational attainment, employment, health, as well as over-representation in government-subsidised housing, urban poverty, exposure to dangerously high levels of pollution of their lands and waters. A disproportionate number of Kanak people live in poverty, despite the fact that many continue to benefit from subsistence practices, and at least 90 percent of the detainees in New Caledonia’s prison are Kanak, half of them below the age of 25.”

As of 2020, unemployment in the Kanak community stood at 38%, with over 8,000 Kanaks living in slum-like conditions in Nouméa. According to the French Institute for Statistics and Economic Studies (INSEE), over 71% of Kanaks lived in poverty as of 2020. Many Kanaks lack the means to achieve upward mobility, in part due to deliberate racial segregation and exclusion policies implemented over the years. Development in New Caledonia lags behind most other parts of France, and there remains a clear pattern of underinvestment in local communities.

Despite New Caledonia’s vast mineral wealth, most of its indigenous inhabitants live in poverty. Image source

Is this the beginning of a protracted insurgency?

Although the intensity and scale of recent violence has subsided, the unrest is unlikely to cease any time soon. Pro-independence groups appear to have little will to champion the use of violence to achieve their goals and are open to electoral reform to achieve them, opening the door to further political negotiations. On May 23, French President Emmanuel Macron visited Nouméa, promising not to force through voting changes as he sought to quell the ongoing violence. Although these moves suggest some semblance of normalcy could emerge in the coming weeks, especially amid the deployment of an additional 1,000 French forces, negotiations to address the Kanaks’ longstanding grievances could be a lengthy process.

Still, the events of recent weeks will no doubt cause a hardened stance among large sections of the populace. The involvement of thousands of young Kanaks in the unrest, who would have only heard of the civil war in the 1980s, indicates that the cycle of radicalization against French policies is very much at an advanced stage. France also appears to be rushing from one bad decision to the next, giving loyalists and independence groups until June to negotiate a settlement and vowing to make a unilateral decision without an agreement between both sides. This ultimatum is unlikely to sit well with young protestors, who continue to speak out amid Macron’s visit.

French President Emmanuel Macron arrives in Nouméa on May 23. Image source

Conclusion

New Caledonia faces a difficult process ahead. The proposed change to elections will only add to the long list of unresolved issues between pro-independence groups, loyalists, and the French government. Moreover, there exists a vast divide between older resistance leaders and the Kanak youth, with the latter much more willing to engage in violence to vent frustrations and achieve their political goals. If Paris continues to push electoral reform, the result could be further protracted violence and a possible insurgency moving forward.

A good in-depth article that I very much enjoyed. I think there are wider geo-political issues that this conflict highlights that I think would be worth more investigation. For instance, Melanesia is currently caught in a period of intense Sino-American competition. China seeking to build influence in the area, the US and Australia on a diplomatic offensive to limit China's influence. Melanesia is a area that Australia's current defence strategy focusses on. The article points out the long-history of armed Kanak struggle and tension has been mediated, rather than resolved for last 30 years. This base of support for independence means that New Caledonia could be fertile ground for an insurgency. Further, nearby French Polynesia another French colony also has a significant underground independence movement. And, the New Caledonia's Melenesian and Pacific neighbours tend to be ex-colonies that spent the 1970a and 80s protesting against French nuclear testing in the Pacific. So there is likely to be little local support for France. A profound concern during a period of Sino-American competition because conflict provides opportunities for de-stabilisation operations. We may already be seeing foreign intervention in New Caledonia, news agencies Al Jazeera and the Guardian reporting the relationship and support that Azerbaijan provides the independence movement. It is also interesting that France shut down Tik Tok on the island. It would great to see you unpack this situation some more. Links to the articles - https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/5/17/france-blames-azerbaijan-for-new-caledonia-violence-unpacking-their-spat

https://www.theguardian.com/world/article/2024/may/17/new-caledonia-riots-explainer-azerbaijan-flags-noumea-link